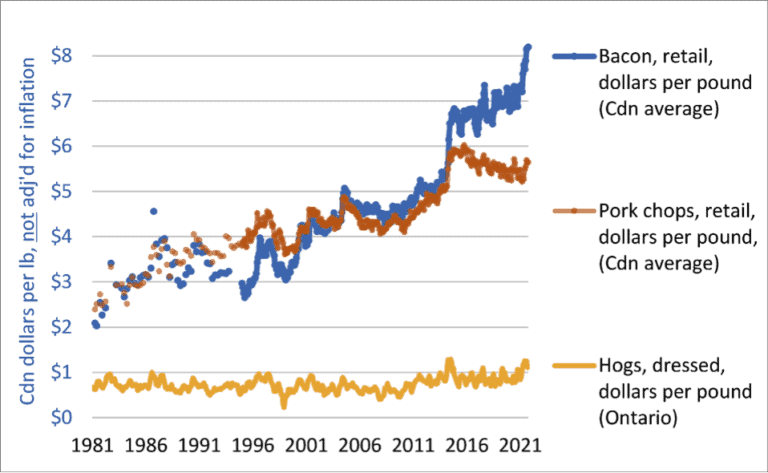

Swift Current, SK—Retail food prices are rising. To explain these increases, many commentators point to rising prices for farm products and cite drought, other production problems, the pandemic, or supply-chain issues. This is not an accurate explanation. Public data shows that corporate food processors and retailers have relentlessly, for decades, pushed up retail prices even as the prices paid to farmers remained largely stagnant.

“Consumers need to know that less and less of the money they spend on food actually makes it back to the farmer. Retail food prices are high because meat packers, other large processors, and big retailers are taking ever larger shares. For most food products, the farmers’ share continues to shrink,” said Stewart Wells, NFU Vice-President of Operations and Saskatchewan farmer.

“Big processors, packers, and retailers are charging consumers more, paying farmers as little as possible, suppressing workers’ wages, and taking more for themselves. That’s why retail food prices continue to increase, not because of rising grain or livestock prices, COVID-19, or supply issues. It’s important that policymakers and all Canadians know who’s behind the rising cost of food,” added Wells.

NFU President and Ontario farmer Katie Ward explained that “Governments’ misplaced priorities have facilitated food sector concentration and paved the way for the high retail prices we’re seeing. Federal approvals for waves of packer, processor, and retailer mergers and the closures of processing plants have increased the power of these corporations. Food price increases are just one effect of this rising corporate power. Another effect, as the pandemic and supply-system shocks have revealed, is that our highly concentrated system is fragile—lacking resilience, diversity, and adequate local and regional capacity and access.”

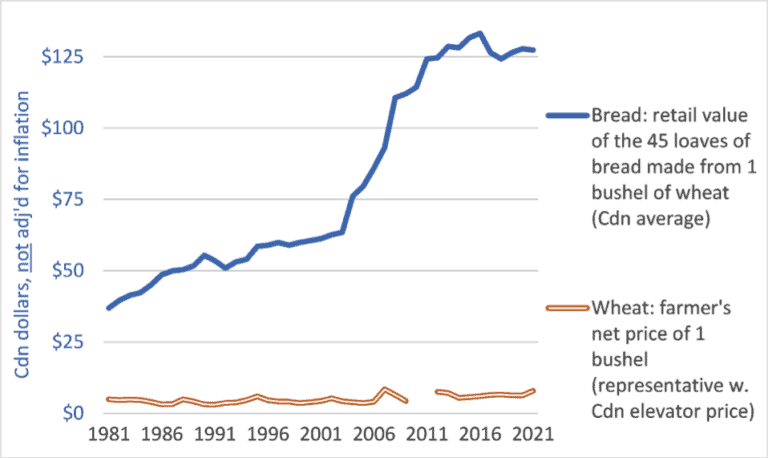

The second graph shows wheat and bread prices. (Source: Stats Can and Gov’t of Sask.) It reveals that wheat prices are not the cause of bread price increases. But the graph hides a more striking fact: through most of the 1980s, Canada still had a two-price wheat policy. While the graph shows that in the 1980s farmers were receiving about $5 per bushel for their wheat—a blended price representing export and domestic sales—Canadian millers and bakers were paying about $7 per bushel for wheat they made into flour and bread. Thus, in the 1980s, millers, bakers, and retailers were turning $7 per bushel wheat into $1 per loaf bread. In recent years, they’ve been turning $7 wheat into $2.75 bread. The farmers’ share is about a third of what it was forty years ago.

NFU President Katie Ward concluded: “Processors and retailers are overcharging because they can; mergers and concentration have multiplied their power. This is creating many negative effects: on farmers, workers, the environment, the climate, animals, and, as rising retail prices show, on all Canadians. To reverse these negative effects, we need smaller scale, local and regional processing, and we probably need the breakup of the largest packers, food processors, and retailers. Rising market power and declining competition has led to steadily rising retail prices; governments must intervene to curb all of these damaging trends.”

The original version of this article can be accessed here.