Just five companies known as the “ABCD group” control 90% of the world grain trade – and the B in this group is about to get much bigger.

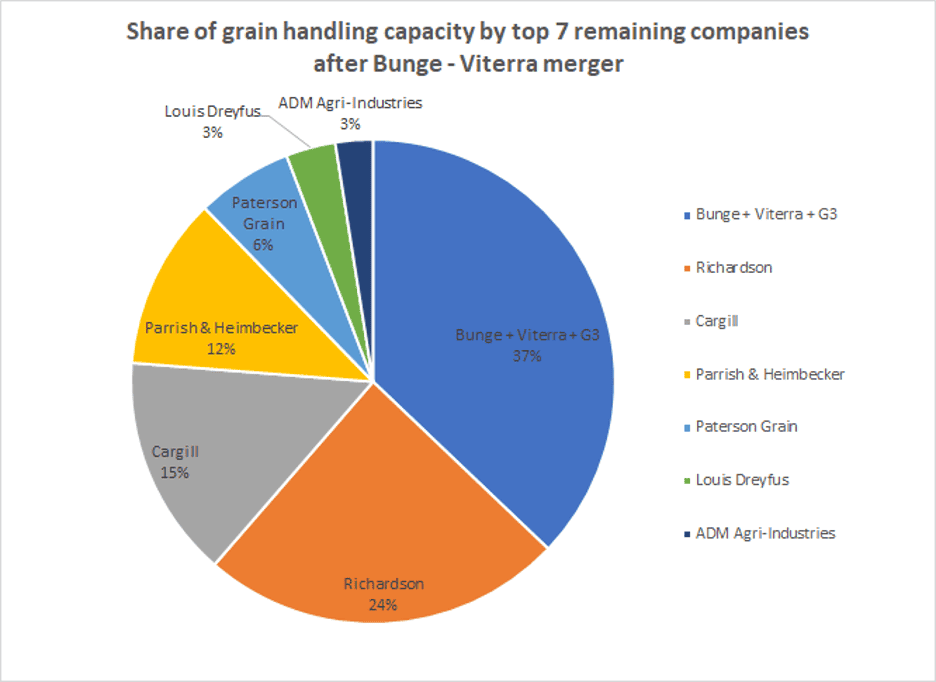

B is for Bunge, which has announced it is in the process of buying Viterra. The other ABCD companies are Archer Daniels Midland, Cargill and Louis Dreyfus, which have dominated the grain trade for over a century, with China’s COFCO joining the list more recently. In Canada, grain elevation and handling has been dominated by five companies from the early 2000s until 2015: Cargill, Viterra, Richardson, Paterson and Parrish & Heimbecker. In 2015 after the Harper government gave Bunge and the Saudi Agricultural and Livestock Investment Company (SALIC) the former Canadian Wheat Board’s assets, the new company G3, moved into fifth spot. Viterra is currently a subsidiary of the Swiss conglomerate Glencore, is 40% owned the Canada Pension Fund Investment Board, and has its headquarters in Regina, Saskatchewan. Bunge’s acquisition of Viterra would leap-frog it into first place in Canada, and move it into third place after Cargill and COFCO on the world stage.

Viterra and G3 are dominant in wheat, while Bunge is dominant in canola, soy and corn. Combining them gives one company massive market power over the largest crops grown in and exported by Canada.

Until 1997, farmers owned close to 60 percent of Canada’s grain handling system through their co-operatives, and until 2012, controlled all exports of prairie wheat and barley through the farmer-directed Canadian Wheat Board. With farmers in charge, the profits from sales were returned to our rural communities and were engines of rural prosperity.

The recent public consultations on Canada’s competition policy highlighted its gaps and deficiencies. Then, the NFU called for changes that would ensure the Competition Bureau prevents harmful mergers, including by outlawing mergers that result in any company having more that 20% of market share in any sector, and prevents companies from using their dominance to exploit smaller players, among other recommendations.

The CR-4 ratio – four-firm concentration ratio – refers to the market share of the four largest firms in a market. If the CR-4 is less than 40%, a market sector is considered to be competitive; if CR-4 is above that, anti-competitive behaviour can be expected. Efficiency gains from economies of scale are not shared with customers, but captured as profits and used to further accelerate consolidation. If the Bunge-Viterra merger goes ahead, we are looking at a CR-4 ratio above 80% in Canada’s grain handling sector.

Today, farmers produce larger quantities and higher value products than ever, but now the vast majority of the wealth created on our farms is being captured by the ABCD traders and the highly concentrated input, farm machinery, financial, and food processing corporations. Their market power has so far not been restrained by Canada’s competition policy. Past mergers reviewed by the Competition Bureau have merely shifted assets between already powerful players. The growing gap between the value farmers create and the value we receive from the marketplace amounts to billions of dollars every year, accelerated by the gap in market power between farmers and the multinationals they must deal with.

In light of the Competition Bureau’s failure to prevent rapid consolidation of market power in the Canadian grain and oilseed sector, the National Farmers Union encourages the federal government to make a counter offer to purchase Viterra and return its assets to the control of Canadian farmers and workers through a new co-operative. This would be in the national interest, ensuring food security and maintaining the proceeds from grain and oilseed exports within the Canadian economy.

In 2018, the Government of Canada purchased the yet-to-be-built Trans Mountain Pipeline for $4.5 billion, and has invested approximately $21.5 billion in construction since then. The government has proven it has the financial capacity to make large investments. Unlike the pipeline, the Viterra network exists, and is operating. For a purchase price of just $US 8.2 billion ($CDN 10.9 billion) – a net annual cost of $CDN 3.94/acre of Canadian farmland over 30 years — Canada would own the world’s eighth-largest grain trading company. Instead of waiting for the Competition Bureau to hive off pieces of Viterra, G3 and Bunge to the other big players in the grain industry, the federal government could create true competition in the sector by ensuring the farmers who produce the commodities will own and control the assets they have created, and regain the market power needed to safeguard farmers’ interests in the international marketplace.