Zimbabwe: Peasant Agroecology transforms Shashe community

Inappropriate seed and seed varieties, the loss of agro-biodiversity, insufficient inputs, degrading soils, and recurrent droughts are just a few of the many factors that have contributed to low crop productivity among smallholder farmers in resource-poor communities in Zimbabwe and much of the global south. Climate change is now making these threats worse. The Shashe Agroecology School for peasant farmers offers hope.

Smallholder farmers in the Shashe area of Masvingo province were familiarised to innovative agroecology interventions, premised on harnessing nature’s goods and services while minimising adverse environmental impacts and improving farmer-consumer connectivity, knowledge co-creation, and inclusive relationships among food system actors.

Holding a notebook while taking notes from one of her colleagues, at one of the beneficiaries’ house from the Shashe Agroecology School farmer, Lina Mudziviri (43) nods her head in happiness as she can’t wait to go back home and implement the lessons she has learnt from one of her fellow farmers during a look and learn field visit in Shashe.

“Before I was introduced to agroecology I would face challenges of raising funds to buy fertilisers and seed to start farming,” Mudziviri said. “Even if I tried using seed from my silo, the seed would not grow because I had no money to buy fertilisers, in some instances I had manure to use because I had no knowledge of how to make my own manure from organic waste.”

Agroecology is a people-centred system of sustainable agriculture and a social justice movement driven by local farmers and other food producers to maintain power over their local food systems and protect their livelihoods and communities.

A large chunk of Masvingo province receives very little rainfall and is in region 4.

“Climate change has affected us, especially the El Nino induced drought, as we receive little or no rainfall, ” said a villager, Abemelek Mutsemure. In this area we have two boreholes that we share as 12 households, thus agroecology has taught me to dig contour ridges that help trap rain water. Mutsemure and other farmers got knowledge on water harvesting techniques. Among the techniques are rooftop rainwater harvesting and surface run-off harvesting, which are now popular with the villagers.”

Elizabeth Mpofu (63), one of the founding members of the Shashe Agroecology School, and the ex-General Coordinator of La Via Campesina, said that in 2016 she was chosen to be the special ambassador for the International Year of Pulses by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation.

“During my term of office, I had an opportunity to visit many countries where La Via Campesina had its members and La Via Campesina had that momentum of coming up with agroecology schools where farmers come together and share their experiences, their challenges, and also come up with strategies on how to adapt to climate change,” Mpofu said. “This is how we also thought it was also important for us to form this agroecology school in Zimbabwe where we gather ourselves there, the rest of the surrounding communities and others who are also coming from far away to come and exchange ideas to see how best we can adapt to climate change.”

Shashe was formed by formerly landless peasants who engaged in a two-year land occupation before being awarded the land by the government’s land reform programme.

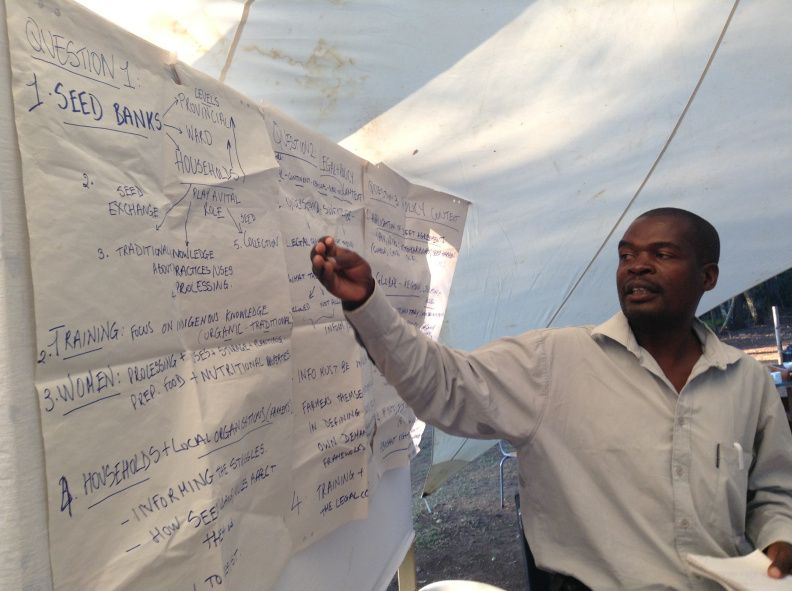

As in the other clusters, the Shashe Endogenous Development Organisation is particularly interested in training other farmers and enhancing a community-based and horizontal learning system.

Hundreds of families are connected, sharing the knowledge gained from their own experience. The initiative was formed to teach women and youth to self-feed themselves or to work for themselves through agriculture using the resources they have at their disposal. They have more than 100 people that they have taught to be self -sustainable.

In the Shashe farming area, smallholder farmers grow a variety of food crops, including grains, cereals, legumes, vegetables, fruit trees and medicinal plants. They also rear livestock, including cows, sheep, goats, pigs and chickens. The grains such as sorghum, millet and rapoko are drought-resistant crops meaning smallholder farmers can still have a bumper harvest even during droughts. During the tour to centres of excellence houses the farmers were taught also how to fish farm and sustain them with recycled waste from their kitchens.

Shashe field officer Chinyoka said: “Farmers are now benefiting a lot from fish farming; we have certain principles that we follow, there is an issue recycling food that we grow, crushing sunflower, and rapoko, thus the food we use to feed the fish. To add on to that we also practise verma culture, creating verma liquids where we keep our worms to feed our fish, furthermore we also take kitchen waste that include sadza and other foods that have no too much salt.”

He added that then fish ponds were designed with plastics underneath to keep the fish warm during cold days. Farmers expressed gratitude to the school citing that the lessons they learnt were insightful.

“With agroecology I no longer stress about searching for funds to buy seeds, instead they will be readily available in my silos,” said Mudziviri. “I have learnt how to preserve them in my house for future use; also I always have plenty of food at my disposal while some of the grains I sell for profit.”

Mpofu said despite receiving poor rainfall, they managed to harvest enough to feed their families.

“You see, and even to sell to other farmers because right now it’s like I have a market where I am also selling some sorghum to some people who did not harvest enough,” Mpofu said. “Also looking in the future, I’m foreseeing a situation where as a farmer and if we are 10 or 12 people or 15, I think we can also manage even to feed the whole machine with our small grains which are producing in this dry area because these crops, we have realised that they do the best with very minimal rainfall and if we have more rains, that means we also harvest more than expected.”

This is an excerpt from an article by Gary Gerald Mtombeni that originally appeared on the news portal Southern Eye on July 7, 2024, and has only been edited for its title.