The Amrita Bhoomi Learning Centre in Karnataka is one of dozens of education hubs around the world providing a space for farmer-to-farmer training in agroecology.

In a wide-ranging interview with Mongabay, the centre’s Chukki Nanjundaswamy discusses their model of agriculture, its Gandhian roots, and how it grew out of the rejection of Green Revolution farming techniques that rely on chemical inputs and expensive hybrid seeds. Nanjundaswamy shares some of their innovative approaches to growing food without inputs, plus clever techniques to thwart notorious pests like fall armyworm.

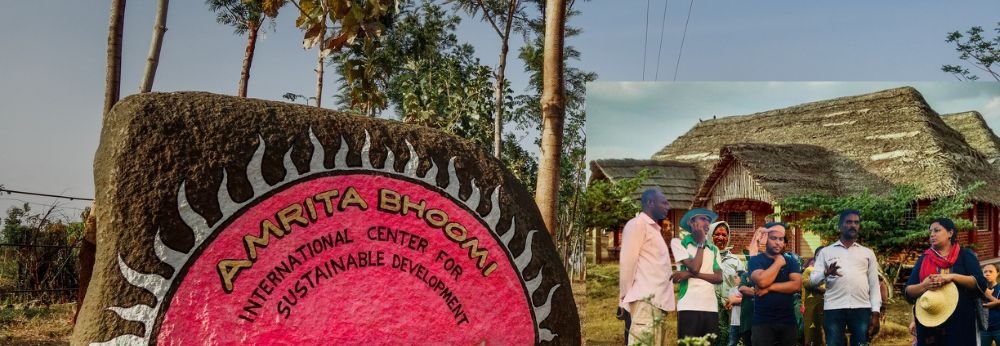

About a four-hour drive southwest of Bengaluru, nestled in a verdant valley near B.R. Hills in Karnataka, Amrita Bhoomi is an agroecology learning centre that offers farmer-to-farmer training focused on agroecology. The centre was born out of organising efforts of the local farmers’ movement KRRS (Karnataka Rajya Raitha Sangha) founded by Professor Mahantha Devaru Nanjundaswamy in the early 2000s. The leadership of this movement envisioned a teaching centre where farmers could share their agroecological practices, learn new techniques, and situate themselves in a Gandhian tradition of organising for social justice.

In 2002, movement leadership purchased the land that the centre still occupies today, a biodiversity haven home to 80 cultivated acres growing dozens of varieties of crops from dryland horticulture – like mangoes and jackfruit – to coconuts and bananas, modelling rainfed farming in lieu of expensive irrigation.

As part of a 2022 series on agroecology for Mongabay, author and sustainable food advocate Anna Lappé had a chance to catch up with Nanjundaswamy. The interview was conducted by Zoom and has been edited for length and clarity.

Here are some excerpts from the interview

The Origins:

“In the early 1990s, the Indian government had opened up its market for multinational corporations, including for agribusiness giants. The American company Cargill was the first to enter India’s seed sector. Cargill started selling seeds like sunflower and corn—all hybrid seeds [so farmers need to purchase them annually] and all expensive for farmers.

India has had long-held traditions of conserving and sharing seeds within the community and family. For the very first time, corporations were talking about patenting seeds and new global trade regimes like the GATT [the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs] were creating frameworks to enable them to do so, to claim intellectual property rights over seeds.

The movement here saw its organising as part of fighting back. In 1993, KRRS conducted one of their biggest direct actions, ransacking Cargill’s offices in Bangalore where the company was headquartered”

Agroecology in Practice: Natural Farming experiences

“When we, the next generation, took over Amrita Bhoomi, we learned from agroecology schools in other parts of the world, in Cuba, for instance, and in South America. In these schools, they use a methodology of farmers teaching farmers. It’s an approach we brought to our work. We also take an intergenerational approach, because most senior farmers were farming pre-Green Revolution and we’re losing that knowledge. They’re a treasure.

For nearly two decades, we have also been a teaching centre for an agroecological practice known as Zero Budget Natural Farming [ZBNF, also known as Community Managed Natural Farming or Subhash Palekar Natural Farming].

We believe one of the reasons why the farming sector is in such crisis is because our so-called agricultural universities are not doing research for the farming community here. They’re mostly funded by transnational corporations and their research benefits those transnational corporations, like Syngenta, Cargill, Bayer [which bought agrochemical company Monsanto in 2018]. Our farmers have nothing to learn from the scientists; they basically all teach Green Revolution technologies [the hyper-reliance on synthetic inputs like pesticides and fertilisers and the use of hybrid seeds.]”

“There are two schools of thought on sustainable farming methods in India. One, organic farming, emerged in the 1980s. Organic farming here had class and caste dimensions, because even though it doesn’t use synthetic fertiliser or pesticides, it does depend on external inputs—often costly ones. It is still an input-based farming system which makes farming expensive and dependent. The farmers’ movement here embraced ZBNF because it is a method that helps farmers become totally self-reliant. It’s not a recipe, there is a lot of scope for farmers to design it according to their own specific conditions, according to their own soil conditions. They don’t have to purchase anything; it’s a knowledge-based technique.

In ZBNF, we refer to fertiliser as a ‘stimulant.’ It is made with jaggery [a traditional cane sugar found in India], some protein, cow manure and urine, and a handful of soil from your own farm. Commercialising it is impossible because you need bacteria from your own farm to multiply. You can’t sell it. In this approach, Mother Earth is everything: you just have to take care of her and nurture her. We just have to give her love.

Making a farmer self-reliant is part of the Gandhian principle of Swaraj which means autonomy. Agroecology is also a fight for such agrarian autonomy.”

“Agroecology emphasises intercropping, multi-cropping, and the symbiotic relationship between crops and the symbiotic relationship with friendly pests. You are creating an environment for your crops to grow happily and to take care of each other. It’s like a traditional, large family; it’s not a nuclear family. It’s a giant family where everyone takes care of each other. This is why biodiversity is so much a part of agroecology.”

Every farmer is a scientist

“We consider every farmer a scientist. To give you an example: the fall armyworm is a notorious corn pest. It’s been causing chaos all over the world. Pesticide companies like Syngenta have been pushing products to deal with it. In the past couple of years, in countries in Africa, farmers who were growing corn started using pesticides for the first time to manage armyworm infestations.

But after only a couple of years of experimentation, farmers here came up with a simple technique: spray the corn with a combination of milk and jaggery in the evening. Ants, attracted by the sweet milk, are drawn to the corn where they discover, and eat, the worms. You don’t need pesticides. To me, this is a great example of a simple innovation by farmers on their own farm.

It’s amazing when you learn about what’s possible to do yourself, when big companies are making millions of dollars selling toxic fungicides or pesticides. We’re told, you can’t grow certain vegetables without pesticides. That’s just not true. We have proven it’s possible with very simple techniques, like the fall armyworm approach or using fermented buttermilk as a fungicide. We have shown you can spray it to control pests on vegetables like cabbage or cauliflower, for example. This is the kind of research we’re doing.”

Here are some excerpts from the interview

The Origins:

“In the early 1990s, the Indian government had opened up its market for multinational corporations, including for agribusiness giants. The American company Cargill was the first to enter India’s seed sector. Cargill started selling seeds like sunflower and corn—all hybrid seeds [so farmers need to purchase them annually] and all expensive for farmers.

India has had long-held traditions of conserving and sharing seeds within the community and family. For the very first time, corporations were talking about patenting seeds and new global trade regimes like the GATT [the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs] were creating frameworks to enable them to do so, to claim intellectual property rights over seeds.

The movement here saw its organising as part of fighting back. In 1993, KRRS conducted one of their biggest direct actions, ransacking Cargill’s offices in Bangalore where the company was headquartered”

Agroecology in Practice: Natural Farming experiences

“When we, the next generation, took over Amrita Bhoomi, we learned from agroecology schools in other parts of the world, in Cuba, for instance, and in South America. In these schools, they use a methodology of farmers teaching farmers. It’s an approach we brought to our work. We also take an intergenerational approach, because most senior farmers were farming pre-Green Revolution and we’re losing that knowledge. They’re a treasure.

For nearly two decades, we have also been a teaching centre for an agroecological practice known as Zero Budget Natural Farming [ZBNF, also known as Community Managed Natural Farming or Subhash Palekar Natural Farming].

We believe one of the reasons why the farming sector is in such crisis is because our so-called agricultural universities are not doing research for the farming community here. They’re mostly funded by transnational corporations and their research benefits those transnational corporations, like Syngenta, Cargill, Bayer [which bought agrochemical company Monsanto in 2018]. Our farmers have nothing to learn from the scientists; they basically all teach Green Revolution technologies [the hyper-reliance on synthetic inputs like pesticides and fertilisers and the use of hybrid seeds.]”

“There are two schools of thought on sustainable farming methods in India. One, organic farming, emerged in the 1980s. Organic farming here had class and caste dimensions, because even though it doesn’t use synthetic fertiliser or pesticides, it does depend on external inputs—often costly ones. It is still an input-based farming system which makes farming expensive and dependent. The farmers’ movement here embraced ZBNF because it is a method that helps farmers become totally self-reliant. It’s not a recipe, there is a lot of scope for farmers to design it according to their own specific conditions, according to their own soil conditions. They don’t have to purchase anything; it’s a knowledge-based technique.

In ZBNF, we refer to fertiliser as a ‘stimulant.’ It is made with jaggery [a traditional cane sugar found in India], some protein, cow manure and urine, and a handful of soil from your own farm. Commercialising it is impossible because you need bacteria from your own farm to multiply. You can’t sell it. In this approach, Mother Earth is everything: you just have to take care of her and nurture her. We just have to give her love.

Making a farmer self-reliant is part of the Gandhian principle of Swaraj which means autonomy. Agroecology is also a fight for such agrarian autonomy.”

“Agroecology emphasises intercropping, multi-cropping, and the symbiotic relationship between crops and the symbiotic relationship with friendly pests. You are creating an environment for your crops to grow happily and to take care of each other. It’s like a traditional, large family; it’s not a nuclear family. It’s a giant family where everyone takes care of each other. This is why biodiversity is so much a part of agroecology.”

Every farmer is a scientist

“We consider every farmer a scientist. To give you an example: the fall armyworm is a notorious corn pest. It’s been causing chaos all over the world. Pesticide companies like Syngenta have been pushing products to deal with it. In the past couple of years, in countries in Africa, farmers who were growing corn started using pesticides for the first time to manage armyworm infestations.

But after only a couple of years of experimentation, farmers here came up with a simple technique: spray the corn with a combination of milk and jaggery in the evening. Ants, attracted by the sweet milk, are drawn to the corn where they discover, and eat, the worms. You don’t need pesticides. To me, this is a great example of a simple innovation by farmers on their own farm.

It’s amazing when you learn about what’s possible to do yourself, when big companies are making millions of dollars selling toxic fungicides or pesticides. We’re told, you can’t grow certain vegetables without pesticides. That’s just not true. We have proven it’s possible with very simple techniques, like the fall armyworm approach or using fermented buttermilk as a fungicide. We have shown you can spray it to control pests on vegetables like cabbage or cauliflower, for example. This is the kind of research we’re doing.”