La Via Campesina Delegation Visited Palestine in December 2024: Notes from their Daily Diaries [Part – 6]

From December 8 to 18, 2024, a delegation of nine peasant-farmers traveled to Palestine, in the West Bank. All their organizations are part of the international peasant movement La Via Campesina, which also includes the Palestinian organization UAWC (Union of Agricultural Work Committees) as a member. For many years, La Via Campesina has stood in solidarity with Palestinian peasants in their struggle against colonization, land and water grabs, and the numerous human rights violations they endure. However, since 2023, the scale of massacres in Gaza and the openly genocidal intentions of the far-right Israeli government have led La Via Campesina to intensify its solidarity work with Palestinian farmers. Organizing a delegation visit to the West Bank thus gradually became an imperative. Due to the obstacles posed by the Israeli state for accessing Palestinian territories, all delegates were European, hailing from the Basque Country, Galicia, Italy, Portugal, Ireland, and France. We, Fanny and Morgan, are both small-scale farmers, based in Ardèche and Brittany, and members of the Confédération Paysanne. The following texts are our journal from these ten days, which profoundly changed our lives and worldview. [ Access all the notes here].

Day 7 – Bethlehem

We wake up at the apartment in Hebron. It was a restless night. We heard gunfire. Mustapha explains to us that an Israeli raid took place at Hebron University and the soldiers put up a banner calling on students to avoid all militant activity.

Here in Hebron, it is impossible not to think about Gaza. The enclave is about fifty kilometres away. Yesterday evening, Fuad told us that they heard the bombardment at night. On a clear day, you can even see Gaza and the sea in the distance.

We get into the minibus to Bethlehem. Our first stop is Dheisheh refugee camp. We are welcomed at the premises of an association that works for cultural and educational development. Kamal explains to us that there are 59 Palestinian refugee camps in the Middle East: in the West Bank, in Gaza, and also in Lebanon, in Syria, and in Jordan. These camps are managed by a United Nations agency, UNRWA. At the Dheisheh camp, there are more than 19,000 inhabitants in an area of less than half a square kilometre. 60% of the population is under 18 years old. The camp was founded in 1949, at the time of the Nakba. Its first inhabitants were people forcibly displaced from 45 villages around West Jerusalem and Hebron.

In the hall at the cultural centre, we see photos of the camp from its beginnings. For many years, it was made up of tents. The inhabitants refused to build solid structures, convinced that they would be able to return to their homes. It was only in the late 1950s that UNRWA built small concrete houses, three metres by three metres in size, each intended for one family.

Nadi explains that Israel was built on the myth of a land without people, and that since 1948, the Israeli state has attempted to mould reality to fit this story, though forced displacements and the extermination of Palestinians. Faced with this situation, the refugees have their memory of the exodus, and the weapon of education. The level of literacy among the Palestinian population is very high. In the refugee camps, the level of education is even higher than among the rest of the population. In Dheisheh, 27% of the inhabitants of the camp are university graduates.

Kamal is 66 years old. He tells us, “I was born here, but my dream is not to die here. I want to see my parents’ village again.” Each family of Palestinian refugees keeps, like a treasure, the key to the house that they had to leave during the forced exodus. The children and grandchildren know the name of their village of origin. And that is how they introduce themselves: “My name is Samir, I live in the Dheisheh camp, and my family comes from the village of…” Nadi adds, “The Israelis think that the old people will die and the young people will forget, but they don’t know us very well. Family plays a very important role here; children grow up with their parents and grandparents, every home is inter-generational, and the old people spend their time telling their story to the youngest.”

Our hosts tell us about UNRWA. The agency plays a fundamental role in ensuring basic services in the refugee camps, for education, health, services for women, and vaccination of children. During Trump’s first term, the United States cut its funding and UNRWA lost 300 million dollars from its budget. The agency survives thanks to voluntary payments from UN member states, but the general budget has dropped severely. The consequences are visible. In Dheisheh, the health centre now only opens one day a week. The situation has worsened further since 7th October. The UNRWA offices in Bethlehem are subjected to Israeli raids almost every month, and you can see bullet holes in the walls. The Israeli government does not hide its intention of closing the UN agency and taking over the buildings to make an Israeli administrative centre in the town. In Jerusalem too, the UNRWA offices have suffered numerous attacks, not to speak of Gaza, where almost all the agency’s infrastructure has been destroyed and hundreds of employees have been killed. Kamal explains to us that the destruction of UNRWA is important for Israel, as it aims to deny the existence of Palestinian refugees and their right to return.

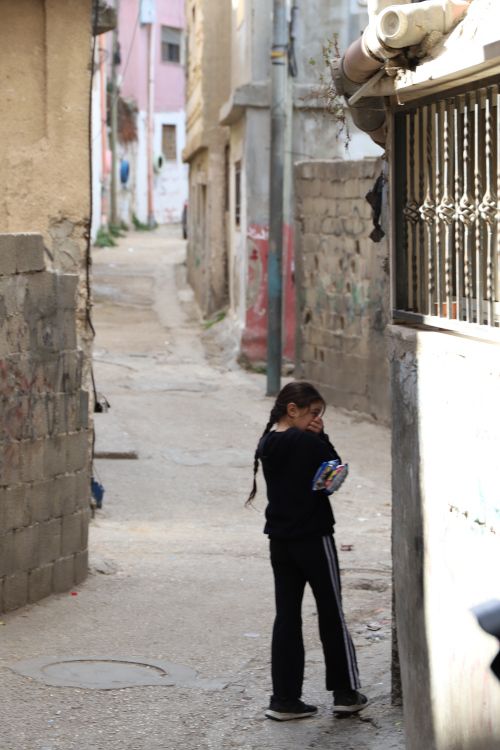

We go out for a tour of the camp. We can see an old security gate, dating from before 1993, when the Israeli army administered Bethlehem, and controlled every entry and exit from the camp. The roads are narrow. The population density is striking with more than 50,000 inhabitants per km². To house a growing population, the Palestinians had to build upwards, and the houses bear the mark of successive addition of new floors. The walls are covered with graffiti. We go into a nursery school. The teachers have done all they can to make the rooms cheery, and they even have a garden on the roof, so the children can see a bit of green.

Three other Palestinians from Ramallah have joined the visit. We introduce ourselves. I explain that I come from Brittany. They have not heard of it. I ask them, “Have you seen Asterix and Obelix?” I often use this reference when I am abroad, and it normally works. But the people I am speaking to have not heard of this cartoon. I explain: “They are Gauls, a group of Celts in the time of the Roman Empire. They are surrounded by Roman military encampments, and they live in the last village that resists the invasion…” Suddenly I realise the clear parallel with the Palestinian cause. We burst out laughing. I tell them about the magic potion, how the two friends travel to support other peoples subjected to Roman invasion, and we start to imagine an instalment about “Asterix in Palestine”.

After warm goodbyes, we make our way to another neighbourhood in Bethlehem.

We stop next to the Wall, opposite the “Walled Off Hotel” created by Banksy. The hotel looks closed, but the Wall is covered with splendid graffiti created by artists from Palestine and from around the world. It is really an ode to freedom. Fuad offers to take another group photo. He looks up at the watchtower and says “There probably aren’t any soldiers today, otherwise we would have had some tear gas fired at us. Let’s make the most of the opportunity!” One picture shows Marwan Barghouti, the most famous Palestinian prisoner. Aghsan explains that he is one of the most popular political figures among Palestinians, and that unlike Mahmoud Abbas, who has lost much legitimacy, he would have the credibility to carry out international negotiations on the future of Palestine. She hopes that he can be freed in the future, perhaps in an exchange of Israeli hostages and Palestinian prisoners.

We carry on walking to another refugee camp, Aida, the entrance of which is marked by a huge gate with a gigantic key above it: the famous key that symbolises the right of return for Palestinian refugees. Opposite this monumental entrance, a few hundred metres away, there is a watchtower. The Wall goes along one edge of the camp. Samir receives us at the premises of a local association in the “Lajee” neighbourhood. He serves us a “maqluba”, a delicious dish of rice, vegetables, and chicken, which is flipped over just before being served. After lunch, he shows us a film about the Aida camp. The 5,500 people who live there, under constant surveillance by the Israeli army, suffer repression almost daily. Tamam tells us that probably more tear gas canisters are used here than anywhere else in the world.

Samir introduces his brother, Khaled, who is 51 years old, and has spent 28 years in prison. He got out ten years ago. Samir is 42, and he has spent 19 years behind bars. This morning too, almost all the men we have met have spent many years in Israeli prisons. Life in the refugee camps is hard: the poverty, the unemployment, and the lack of prospects lead many young people to choose the path of armed resistance. However, just an activity run by an association, or waving the Palestinian flag can also lead to imprisonment. The refugee camps are regularly raided by the Israeli army, and young men are particularly targeted. The law is applied in an arbitrary way. Samir explains to us that for Palestinians there is no civilian justice. They all appear before Israeli military courts. A high proportion of prisoners are waiting for trial, and remain in administrative detention for years. There are currently thought to be more than 10,000 Palestinian prisoners. The proportion of adult Palestinian men who have been in prison since 1967 is said to be as high as 40%: this means that everyone has a brother, a father, an uncle, or a cousin behind bars.

Khaled tells us about the conditions in detention. Hunger, thirst, torture, illness, and prison overcrowding mean that many of them do not get out alive. These conditions have worsened since 2023. It has become almost impossible to visit people in detention. Lawyers who attempt to meet their clients are threatened. To survive, Palestinian prisoners have implemented strict discipline: “No sleeping in.” Prisoners force themselves to play sport and to study, so much so that Samir says that “prison is the university for Palestinians”. “In prison, we have the chance to be with an impressive number of university lecturers, so you can learn whatever you want!” They particularly learn to speak Hebrew there, as knowing the language and culture of the occupier is a question of survival.

Samir then takes us to the roofs of a house in the neighbourhood. There we find a little kitchen garden. Fuad is proud to show us one of the key projects of UAWC for urban agriculture, intended to produce vegetables and greens for the population of the refugee camp. We enter a greenhouse where a hydroponic cultivation system has been set up. As everywhere else in Palestine, what is lacking is water. Not a drop is wasted here, as any water that is not absorbed by the plants goes into the irrigation system, in a closed circuit. Space is another limiting factor, and a lot of growing is done vertically. It is a very smart technique, all carried out using recovered material. We are amazed. OK, so it’s not organic, but in the conditions of a refugee camp, hydroponics seems like a very useful technique.

Colourful benches made from pallets brighten up this little paradise. However, if you look around, you notice that on this roof we are within range of the nearest watchtower. Indeed, a few years ago, a child was killed by a bullet fired from that same watchtower by the large gate. His portrait is there, under the UN flag, next to the door to the school.

Samir takes us to the minibus. Fanny and I keep asking him questions. “How does it feel to be freed after such a long time?” “Of course, I was happy to see my friends and family again. Since then I have got married and I have children. But look around you: the walls, the watchtowers, the barbed wire. Can you really call this freedom? And as I am an ex-convict, I cannot leave my neighbourhood. If I pass a checkpoint, and they ask me for my papers, it’s too risky. I can hardly go anywhere. I would rather die than go back to prison.”

This visit left us stunned. However, as is often the case during our visit, the hardest points are accompanied by more relaxed moments. Fuad has decided it would be unthinkable to come to Bethlehem without going to see the Church of the Nativity. As our delegation does not know the story of Jesus very well, it’s time for a bit of religious education. We walk across a busy market, then we enter the old town. The atmosphere is warm and relaxed. Here at least, we are not in the firing range of an Israeli soldier. We stop to have a drink of fresh fruit juice. Fanny and I take photos in “tourist mode”. Many inhabitants say hello and welcome us. Carlos takes some selfies with the juice seller. We are surprised not to see any Christmas decorations, as we are well into December, but the local council in Bethlehem has decided to limit costs. It is also another way to express solidarity with the inhabitants of Gaza, by not having a big celebration while the massacres continue.

We reach the Church of the Nativity. The esplanade is normally crowded with a mass of pilgrims. Now it is almost empty. A guide takes us inside the church, and we process through to the grotto where Jesus is thought to have been born. A star marks the exact spot where Mary is thought to have given birth. Opposite is the manger that is thought to have been used as a crib. I would never have imagined that one day I would find myself in one of the most sacred places in the world. A child, a grotto, a book: the stories that shape our societies are based on these small things…If only the life of all the children in Palestine could be protected as if they were prophets.

Night falls. We set off for Hebron.

Aghsan has been telling us about local handicrafts and we take a break in a ceramics shop. It is the trader’s lucky day: we clear out his shop. Carlos tries to negotiate the price of a slightly chipped cup. The seller answer “It is like me, like all of us, we are all a little broken here.” A glass blower is working in the workshop. He falls for Fanny’s charms, and offers her a little glass heart.

When we return to the apartment, Fuad has a surprise for us: he has all the ingredients to make the famous knafeh. After a hearty dinner, he brings in the dessert, decorated with “LVC” for La Via Campesina. We enjoy the feast.

Notes by Morgan