Argentina : “Without land and water in our hands, hunger advances”

This interview was originally published on the Agencia Tierra Viva website

The work of rural women, their role in building food sovereignty, and their daily lives in the territory are some of the key issues addressed by Carolina Llorens from the National Peasant Indigenous Movement (MNCI-ST). Ahead of another March 8, she highlights the specific challenges of rural struggles and issues a call to action: “Feminisms need to become peasant-like.”

“Sowers of Life and Resistance” is a booklet featuring testimonies from women who participated in the first edition of the Feminist School, organized by the Alliance for Food Sovereignty of the Peoples of Latin America and the Caribbean. The booklet explores feminist economics, agroecology, and the fight against gender violence and racism, drawing from the experiences of those who produce healthy food.

The Feminist School was conducted through virtual sessions and an in-person gathering in Colombia in 2023, with a strong focus on young women’s participation. “Although young women build food sovereignty daily, their voices are often absent from international discussion forums. We wanted to amplify their participation,” explains Carolina Llorens, a member of the National Peasant Indigenous Movement – We Are Land (MNCI-ST) and one of the school’s coordinators.

Young peasant women, family farmers, Indigenous women, and artisanal fisherwomen from Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, and other countries took part in the experience. “Each of them was able to share the knowledge they have cultivated in their territories. For us, the struggles they lead give us hope,” she says.

The booklet “Sowers of Life and Resistance” calls for depatriarchalizing food systems, advocating for alternatives such as agroecology to advance food sovereignty.

What does it mean to depatriarchalize food systems?

—It means recognizing the oppression embedded in these systems—from production to consumption—and making visible the many tasks performed by women, such as caring for land and seeds. Women’s work is often unrecognized and absent from decision-making in marketing and industrial production, the most profitable sectors. Yet, these sectors do not produce food—they produce commodities.

Food is what nourishes us, but the industrial and capitalist agri-food system prioritizes mass production that lacks nutrients, benefits large monopolies, and undermines both nutrition and food sovereignty.

Depatriarchalizing food systems means questioning these power structures and building alternatives that do not perpetuate violence against people or ecosystems. Agroecology and fair trade are key steps in this transformation.

How do these power dynamics affect women producers?

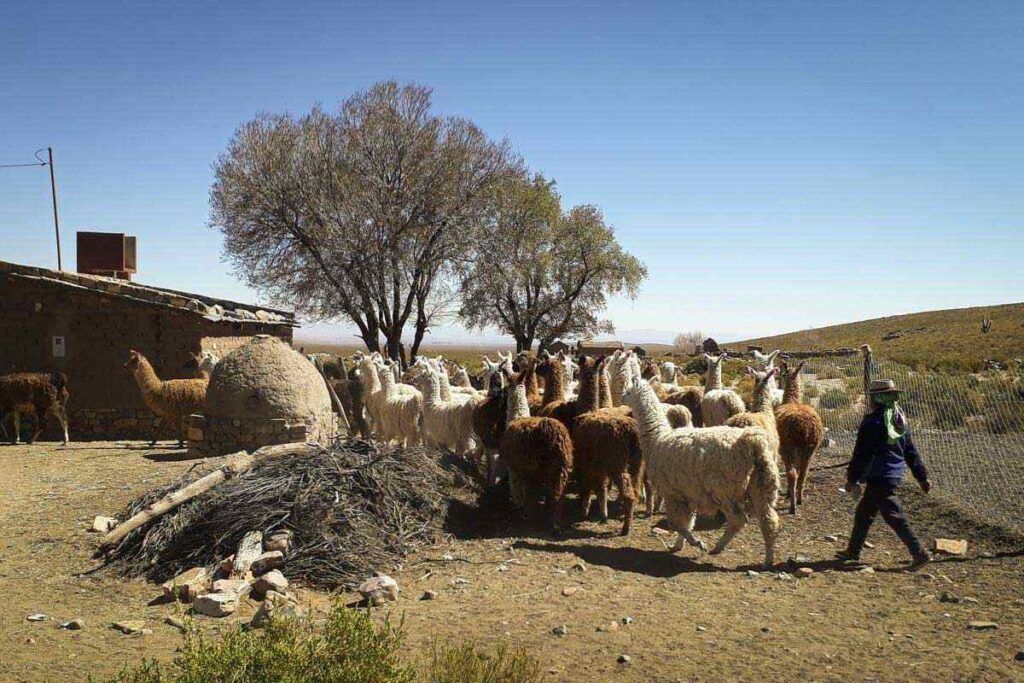

—A clear example can be seen in Córdoba, where I live. Goat herding is a task primarily carried out by women, children, and young people, yet it is not considered a productive activity but rather an extension of household duties.

This perception denies women autonomy over sales, which remains under the control of the male head of the household. To challenge this, the Peasant Movement of Córdoba (a member of MNCI-ST) has been working toward economic autonomy for women producers—first by making their labor visible, then by adding value to goat farming through milk and dulce de leche production. These foods are made and sold by the women themselves, granting them economic independence and, in turn, autonomy over their bodies, their decisions, and their land.

Why is agroecology key to depatriarchalizing production?

—Because it promotes a model of food production based on interdependence and eco-dependence. Agroecology preserves ecosystems and prioritizes caring for life. It aligns with feminism because centering care—both for the environment and for relationships—fosters a non-exploitative approach to food production.

Unlike organic farming, which primarily focuses on chemical-free production, agroecology considers the entire system—not just growing healthy food, but also fostering just, non-hierarchical relationships between those who produce it.

How does peasant feminism contribute to the fight against fascism and racism?

—For over 500 years, peasant, Indigenous, and Afro-descendant women have fought for dignified lives and collective well-being. Peasant, Indigenous, and popular feminism uplifts and makes visible these ongoing struggles—rooted in daily life and survival within our territories.

Urban feminism often remains disconnected from the realities of rural life and, at times, unintentionally reproduces systems of oppression, continuing to silence rural women’s voices. For instance, rural women perform four to five extra hours of unpaid care work daily, yet public policies fail to acknowledge this.

Feminism must become more rural, recognizing the oppressions faced by rural and Indigenous women and integrating the struggle for food sovereignty into its broader fight for justice.

The booklet amplifies the voices of these women on care work, feminist economics, multiple forms of violence, political advocacy, and their crucial role in defending food sovereignty.

What are the key priorities for peasant feminisms in Latin America today?

—In the face of rising fascism, which exacerbates violence against women, LGBTQ+ communities, and our territories, we must strengthen our alliances.

The priority today is to unite our struggles—defending our rights and food sovereignty alongside urban popular feminisms and climate justice movements. We must highlight the central role of peasant and Indigenous women in sustaining life.

Without our bodies defending territories and common goods, extractivism and the climate crisis will continue to advance. Without land and water in our hands to produce healthy food, hunger will spread.

The struggle for food sovereignty, agroecology, and a life free from violence is fundamental to resisting the capitalist, racist, and patriarchal corporations that threaten us all.