Today peasants, indigenous peoples, farm workers, land-less peasants, fisherfolk, consumers, women and young people worldwide are faced with difficult challenges.

Increasingly, in the four corners of the planet, people are feeling the effect of the growing imposition of financial and market paradigms on every facet of their lives. Subjugation to the interests of capital has led to the acceleration of capitalist extractivism, including industrial farming, livestock and fishing; large scale mining; mega-projects such as hydroelectric dams, large scale solar panel farms, tourism and large scale infrastructure – and to massive land grabbing and a changes in the way land is used. To an increasing extent, the control of common goods, which are essential to the lives of people and nature, are concentrated in the hands of a few private actors who have easy access to capital, with disastrous effects on the people and their rights.

Furthermore, the highly concentrated market conditions (of consumable goods and the commercialisation of products) increasingly exclude small scale producers. Women and young people are by far the worst hit by these actions. The food, climate, environmental, economic and democratic crises that all of humanity is facing show clearly that a transformation of the current agricultural and food model is vital.

In many places, the people who defend themselves against and resist this “development” model face being demonised and criminalised, which in turn leads to prosecutions, imprisonment, violence at the hands of state or private security forces, and even murders. These are not random “incidents”, they are occurrences reported by almost every organisation. In this respect, States are not only failing in their duty to protect the people from these outrages, but are in fact important actors in advancing this model.

These effects are not a “natural phenomenon” of globalisation, they are the consequences of a political framework that responds to the paradigm of continuous growth: in our analysis we find, amongst others, increasing commercialisation of land and water that favours grabbing; policies that favour the privatisation of seas and continental waters; the privatisation of seeds through patents and plant breeders’ rights, and agricultural and fishing policies that favour large scale production. These policies are reinforced within the framework of Free Trade Policies and Bilateral Investment Treaties.

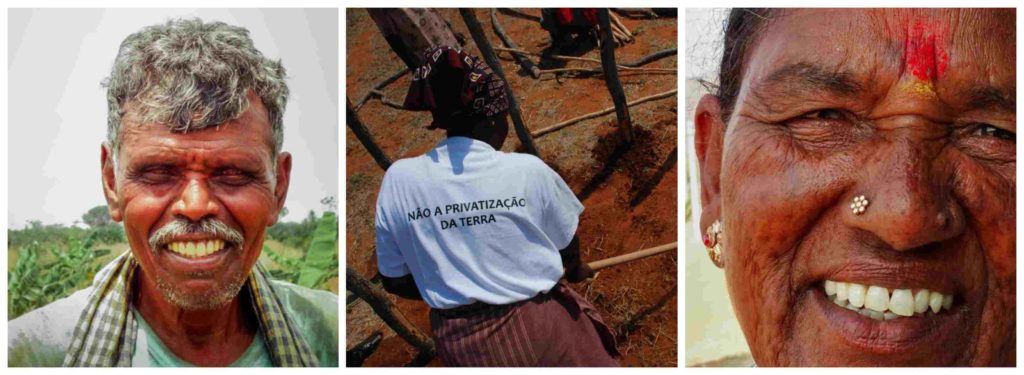

But struggles on a local and global level have also grown stronger and there is widespread resistance with many success stories. La Via Campesina’s actions as a transnational social movement, have made it possible, through exchanges of experiences between organisations and social movements, to strengthen struggles, to analyse these policies and their mechanisms more deeply and to develop collective visions and proposals.

On the one hand the new context, the fact that capital is becoming more deeply rooted in the countryside, with a new alliance of national and international actors, and, on the other hand, the continued exchange of experiences and dialogues among our knowledges (called diálogode saberes), have led to a more profound analysis and to a broader vision of our proposals for agrarian reform.

Both the “object” of agrarian reforms, and “who” needs to bring them about have changed. Whereas historically the organisations’ proposal for

agrarian reform referred particularly to land distribution and to access to productive resources, such as credit, financing, support for marketing of products, amongst others, the integral or genuine agrarian reform is based on the defence and the reconstruction of territory as a whole, within the framework of Food Sovereignty. The broadening of the object of agrarian reform, from land to territory also broadens the concept of the agrarian reform itself.

Therefore the contemporary proposal for integral agrarian reform does not only guarantee the democratisation of land, but also takes into consideration diverse aspects that allow families to have a decent life: water, the seas, mangroves and continental waters, seeds, biodiversity as a whole, as well as market regulation and the end of land grabbing.

Furthermore, it includes the strengthening of agroecological production as a form of production that is compatible with the cycles of nature and capable of halting climate change, maintaining biodiversity and reducing contamination.

In the areas where there is still an unequal distribution of land, people are fighting for redistribution based on the expropriation of large estates. Land tenure, depending on the territories, can be collective, individual, or co-operative. There is also the possibility of granting co-operatives and peasants use rights to the land. In areas where the people do have access to land, the question is one of defending their territories against land grabbing.

Furthermore, the vision of who needs to carry out the agrarian reform is changing. Until the year 2000 there was a wide consensus to the effect that democratically elected governments should be the prime actors carrying out the reforms. Nevertheless, the current processes, that have

led to major power imbalances, increasingly demonstrate that only a powerful popular movement, that is both rural and urban, can assure that such a process is carried out.

The analysis is also based on past agrarian reforms: both socialist and classical reforms have had their limitations. In many countries classical reforms that were based on the common economic and political interests of peasants and sectors of urban industrial capital were carried out – the latter with the aim of restoring productiveness to unproductive large estates and creating an internal market for their industrialised products.

With the changing of the agroindustrial model towards a transnationalised economy, which intensifies the use of common goods on a large scale, and where there is a growing alliance between transnational financial capital and the national elite, an agrarian reform is no longer considered to be necessary in the eyes of capitalists. On the basis of this analysis, strategies are increasingly focused on carrying out an agrarian reform that is driven by social movements. Depending on the political context in which organisations act, most do not rule out intervention in public policies, but they reinforce strategies for change from the grassroots level: direct actions, such as occupying land, marches and protests and other forms of civil disobedience; the praxis for change, such as building production systems that are compatible with the cycles of nature, solidarity trade relations and supportive social relations; the democratisation of knowledge and social relations free of oppression, which aim to revert hierarchical, racist and patriarchal logic. The strategies also include the promotion of a different kind of communication from that of the mass media, and of another research model, from a land-based perspective.

With the fight for Food Sovereignty there is an increasing convergence of struggles seeking to achieve a correlation of forces that will allow them to move towards a political system that favours the common good. In this respect, it is evident that integral and popular agrarian reform is understood to be a process for the building of Food Sovereignty and dignity for the people.

Extracted from the publication Struggles of La Via Campesina for Agrarian Reform and the Defense of Life, Land and Territories