Paraguay: Prolonged Struggles Against Eviction and Imprisonment of Indigenous and Peasant Peoples

Conamuri militants denounce the criminalization of those who struggle for land rights in Paraguay and report on resistance experiences

By Alicia Amarilla, Bernarda Pesoa and Perla Álvarez (First published by Capire)

We are currently engaged in struggles to demand revocation of Law No. 6,830, known as Zabala-Ribera Law, which criminalizes people who struggle for land rights. The law amends article 142 of the Criminal Code and increases the maximum prison sentence for criminal trespass from five to ten years, with no trial. The amendment was approved within less than eight days. Big soy and livestock landowners, organized in producer associations, exert their influence on public policies and amend laws according to their interests to jostle populations out of their lands.

As soon as the law was approved in September 2021, several Indigenous communities were evicted. People are now living on the streets of the capital city. Women, particularly young women, are now in a situation of sexual exploitation. Children are begging. Meanwhile, people who struggle to defend their territories are criminalized and accused of criminal trespass.

There is no longer an eviction protocol with a previous notice, which would allow people to defend their production, their animals, their houses. Eviction now occurs without any notice, conducted by the Armed Forces and business owners, who burn houses while the bulldozers plant soybean. They burn traditional graveyards and plant soy over the areas.

Less than one month after approval of the law, the Ka’a Poty community was evicted for the second time. Indigenous peoples and communities marched in favor of the Ka’a Poty. There have been clashes with the Armed Forces and their riot squads, leaving many people wounded. The law grants even more power to the Armed Forces of Paraguay, because the military are the big landowners’ body guards.

Officially, there are more than 800 Indigenous settlements and communities to be evicted. This number is a result of the inaction of institutions such as the Paraguayan Indigenous Institute [Instituto Paraguayo del Indígena] (INDI), the Ministry of Agriculture, and the Public Prosecutor’s Office, and of the existence of “tierras mal habidas”, public lands distributed to government allies during the dictatorship. Revocation of the law is not going to entirely change this situation. This is why we demand evictions to be suspended for at least one year, period over which we may advance into regularization of settlements.

The Main Point of a New Wave of Struggles

In 2021, social and peasant organizations joined forces to analyze our situation during the pandemic. Political, economic, and social matters changed; some laws were approved amid the pandemic. As to economy, the result is the advancement of agribusiness into our territories. This is the motivation for the law amendment.

Our situation is quite unfavorable in political terms. We have been subject to oppression and repression, resulting in political imprisonment due to struggles for land. The Public Prosecutor’s Office is one of the three national branches and has been strongly supporting the narco-politics and the forced evictions in Indigenous communities. Paraguay has become a narco-state. This is the face of capitalism we confront.

Indigenous communities supposedly have the support of the INDI, but the institution also has no power to defend the communities when a judge or prosecutor orders forced eviction.

There are, in Paraguay, more than 21 Indigenous peoples with different cultures and languages. Those who have fertile territories, forests, and springs are chosen by transnational companies to produce transgenic soybean and extensive cattle farming. Unfortunately, the use of hit men is increasingly commoner in the countryside. Farms, houses, and communities are burned to prevent struggles for Indigenous lands. Educational institutions and sacred places where the elderly offer up their prayers have been burned. Houses built years ago have been demolished, as well as their crops. It is also very significant that, during the evictions, they destroy water wells and springs.

This has united us. In November, we managed to hold a big national en banc session, gathering peasants, people from the cities, and Indigenous peoples. We organized a big mobilization on December 10, International Day of Human Rights. Millions of us went to the streets to demand the end of violations. There we announced we would have big mobilizations in March.

We started with March 8, the International Day of Women’s Struggles, and, on March 9, we continued the prolonged struggles. We call them “prolonged struggles” because they will not end, and because we know that only with the grassroots strength will we succeed in revoking the criminalization law.

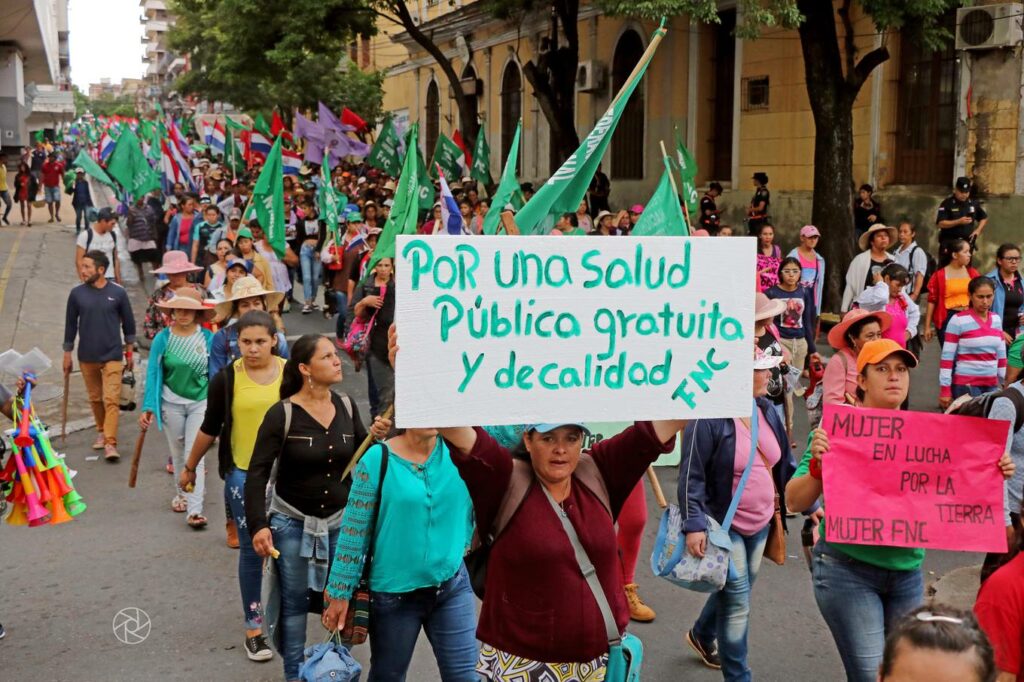

On March 24, we organized a peasant, Indigenous, and grassroots march, uniting our forces. This was a historic march that gathered 20 thousand people, a big crowd in which bravery prevailed over tiredness and hunger. It is not easy to mobilize 20 thousand people in Asunción: it requires an extraordinary organization process. A big part of this articulation process is related to La Via Campesina and its national organizations: the National Coordination for the Organization of Women Workers, Rural and Indigenous Women [La Coordinadora Nacional de Organización de Mujeres Trabajadoras, Rurales y Indígenas] (Conamuri), the National Peasant Federation [Federación Nacional Campesina] (FNC), and the Organization of Land Struggles [Organización de Lucha por la Tierra] (OLT) are the political leadership of the march.

Unity and organization are key in promoting security

The prolonged struggle extended for 16 days of activities. Over these days, we saw how people have been resisting, whether they are children, young people, or leaders standing by their people. Roads were blocked in 60 places throughout the country during these days. In the camp, we struggled with basic needs, rains, and storms, but we also had beautiful grassroots meetings. We resisted everything, and we are now briefly retrieving, that is, we are coming back to our territories to get ready and proceed.

The Claims of the Prolonged Struggles

We demand a dialogue with the three branches of government. We have taken the floor, but no permanent agreement was achieved. The evictions have been suspended for now, but we do not know for how long.

Freeing people who have been imprisoned for struggling for their lands is a matter of urgency. We demand a discussion on an agrarian reform policy to regularize settlements.

Our claims include the negotiations around the Itaipu Binacional hydroelectric plant, since 2023 will be the year for new agreements related to its financial basis. We request our grassroots sector to be represented in the negotiations and we defend the sovereignty of Itaipu and the energetic sovereignty of the Paraguayan people. The Bioceanic Route, which extends between Brazil and Bolivia, is also a point of attention, since it crosses Indigenous communities, destroying them all.

We also demand public policies regarding production, as climate change is striking our country. We have been through droughts during production season; we lost seeds and crops. Big producers are backed by subsidies, while peasant, Indigenous, and grassroots organizations have no response from the government. We have not yet obtained a public policy to guarantee Indigenous peasant production that goes beyond assistance and distribution of staple baskets for short periods.

Climate change also affects women’s lives. Our solidarity and feminist economy, with local fairs and trade, is our source of income. But now that we do not have production neither seeds or inputs for craft work, poverty affects us much more, particularly Indigenous women.

Massive Organization

Participation of Indigenous peoples in this prolonged struggle has been striking. The joint organization forces of social urban, peasant, and Indigenous movements have come to fruition 20 years after the articulation process against privatization in 2002, when six laws on privatizations were being simultaneously discussed in the Parliament. Since then there have been hundreds of mobilizations of all types revolving around the matter of land and agrarian reform. “But now the articulated struggle happens once more.

We were sick and tired of that, and people were happy to contribute to this hand to hand struggle. When the people becomes fed up with all these injustices, as we are now, when the people rises, when the people raises its voice, no one can say ‘no more’ until the goal is achieved. Strengthening a collective political subject is key for the peasant people.

This sexism displayed by our partners and about which we complain also emerges in the relationship between the state and the people. Many communication media reported that women are the face of this struggle. Many women are engaged in confrontations in the settlements, landless commissions, urban settlements, Indigenous communities. The mixed organizations that were with us in the camp talked a lot about violence issues during grassroots meetings. This concern with feminist matters in mixed spaces is new and very interesting.

March, in addition to being the month of women, is a historic month of struggle for peasant people. The first big peasant march after the end of the dictatorship took place in March 1994 and gathered 50 thousand peasants in Asunción. Here, March 8 was the day of the women’s mobilization, and the journeys started on the 9th. It was an exercise of acknowledgment and consideration, which shows one more step of the men who are side by side with us. Our feminist sisters, both from the countryside and the cities, who led the mobilization embraced the peasants’ proposals as their own. Our feminist sisters have shown solidarity to us, in a connection mostly promoted by Conamuri.

They play an extraordinary leading role in these journeys. The camp involves a learning process on the collective work, on coexistence in extreme conditions, but also on the collective resolution of political and daily issues.

We women have always been engaged in the big struggles, but have never been acknowledged. Now there is this acknowledgment because there is a collective work: women take the floor, demand, propose, insist.

April 17, International Day of Peasant Struggle

The struggle for food sovereignty, peasant rights, unity, and solidarity against hunger marks the call made by La Vía Campesina on April 17th, International Day of Peasant Struggles. Since 1996, La Vía Campesina has marked this date to keep memory alive and denounce the now 26 years of impunity since the Eldorado do Carajás massacre, in Brazil, when 21 landless people were killed. To this day, stories like this one continue to happen in countries such as Colombia, Paraguay, the Philippines, Brazil, and Honduras, where thousands of peasants and Indigenous people are criminalized and murdered for defending the land and common goods to grow healthy foods for their peoples.

With the motto “30 Years of Collective Struggle, Hope, and Solidarity,” La Vía Campesina celebrates its anniversary as a global movement and calls for unity in action across the world. Symbolic actions are planned to take place throughout April, such as food donations, farmers’ markets, discussion panels, planting of native trees, seed exchange. These actions are also part of the denunciation of the industrial food system and agribusiness.

Bernarda Pessoa is from the Toba Qon people; she works with communication and culture at Conamuri and is currently department coordinator of the organization in Presidente Hayes. Alicia Amarilla lives in the Caaguazú department and is a member of the national management of Conamuri. Perla Álvarez Britez lives in Caaguazú and participates in La Via Campesina on a regional and international basis as a representative of Conamuri.

Edition by Helena Zelic

Translated from Portuguese by Rosana Felício dos Santos

This post is also available in Español.