Negligence, injustice, and insensitivity – Peasant situation under coronavirus crisis

The coronavirus has exposed the injustice against the peasants, waged workers, and the poor by governments across the world. Neglect of and insensitivity to the situation of these groups is appalling. The support measures are inadequate and late. Several members of La Via Campesina have issued statements highlighting the precarious situation of peasants and migrant workers around the world

Their children’s education too, due to limited access to the internet, is disproportionately affected. The global public health sector is in a critical state, following many years of cuts in social spending and privatisation. The sector simply has failed to cope with coronavirus pandemic. Testing for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is inadequate because of capacity limitations, mostly in developing countries. There is an apparent lack of solidarity among member states.

Overview of the general situation in La Via Campesina regions

The urban areas are most affected by quarantine measures. In Africa, the rural areas (countryside) people are still going about daily chores such as fetching waters, taking animals to the pastures to graze, attending to their fields, but observing social distancing between homesteads. In Central America, despite the travel restrictions, food producers are still able to move, but face immense challenges in accessing local markets.

Food is already lacking for people who live off their salaries. Recurring droughts due to climate change worsens the situation. Many countries in Africa and Latin America did not receive adequate rains in 2019. Central and local governments in South East and East Asia are starting emergency relief programs to support the poor. Conditions for the working class is precarious.

Europe has been affected differently. Countries such as Italy, France, and Spain are worst affected, Germany to some extent. All countries are locked down. Spain, Italy, and France imposed stringent quarantine measures. Public health has reached its limits. Italy was left alone to deal with the pandemic, and this puts a lot of pressure on the EU system.

Militarisation has increased in some regions (e.g., Central America), so has the crime and criminalisation. Some governments used the crisis to militarise further, deepening authoritarianism. In the Philippines, the president called for the shooting of those not obeying lockdown measures.

In North America, the US has been affected the most. The vulnerable populations (the migrant workers, farmworkers, the poor, prisoners, etc.) are worst affected. Hunger is now widespread in the US. Joblessness runs into millions.

In the Caribbean, Haiti faces increased insecurity and runaway inflation. The health system is near collapse. The country, because long draw protests, lacks the most basic facilities and services to provide water and sanitation. Staying at home is very difficult during quarantine, and many people will starve to death.

Cuba is promoting solidarity and has sent medical personnel and medications to help other countries (Nicaragua, Italy, etc.) to fight coronavirus. Asociación Nacional de Agricultores Pequeños (ANAP) of Cuba is working with medical professionals to organise health camps to create more awareness among its members and communities. In Honduras, communities are sharing traditional medicines as the public health system has failed.

In South Asia and Latin America, cases of domestic violence, especially on women and children, have increased. Mexico has recorded the highest domestic violence cases, including femicide.

Peasant farmers’ markets closed abruptly, few re-opened

Despite peasants producing the bulk of the food consumed globally, farmers’ markets were shut down following lockdown restrictions to stop the spread of coronavirus. Many peasants now have fewer places to sell the produce. Tonnes of fresh produce spoilt in the fields, some confiscated and destroyed by the authorities in an attempt to dissuade movement. However, some governments (e.g., Zimbabwe, South Africa, etc.) have since relaxed the rules to allow some urban farmer’s markets to open. These countries are putting some measures to help coordinate the collection and distribution of the farmers’ produce.

Supermarkets and big commercial farmers have benefited disproportionately from governments’ support programs. Such has been the case in most countries in Africa, Europe, Asia, and the Americas. Canada and the US have put measures to avoid the closure of large farms and ensure food deliveries.

In Japan, a country that depends on cheap food imports, citizens realise how vulnerable the food system is. It is an opportunity for strengthening the call for food sovereignty. In South Korea, peasant farmers are having difficulties finding a market for their produce. They used to supply local schools, but now they are closed. So were the peasants in Japan. Korean Peasant Women League and others are asking their government for compensation.

In Europe, many municipalities closed local markets, the main markets for peasant farmers, along with restaurants and canteens. European Coordination Via Campésina (ECVC) members are pushing for opening the markets. Some of them ask supermarkets to open to local peasant food. Also, supermarket workers are in a difficult situation, as they are exposed to the risk of getting infected, and some of them went on strike. In France, there is a campaign to re-open farmers’ open-air local markets and developing guidelines on how to act in the context of COVID-19. One of the political demands is the regulation of prices and sectors.

In Panama and Honduras, due to food shortages, speculation has increased. However, not all governments have put harsh restrictions. Indonesia, Malaysia, and Timor Leste, peasants continue to work in the fields and market their produce. In Indonesia, SPI has called its members to uphold food sovereignty, keep producing, and meet the local production.

Exploitation and insensitivity to the plight of seasonal, casual and migrant workers

Countries such as Spain and Germany are dependent on migrant and seasonal workers as agricultural labour. Most of the workers come from Eastern Europe (Bulgaria and Romania, etc.). UK and France are asking their citizens to fill the labour gap but with limited success. Most west European populations shun agricultural work because of low pay without respect for fundamental rights. Romania has started charter planes paid by agribusiness companies to western European countries. This attitude presents a lot of ethical problems. The migrant workers are stuck in “camps”, without essential services, and in very precarious conditions. Portugal decided to regularise all undocumented migrants to allow harvesting of crops and avoid losses. These migrant and seasonal workers lack protection and safety and, are highly likely to be infected with COVID-19. Now is an opportunity to denounce the agricultural model and exploitation of the migrant and seasonal workers and the current injustice. ECVC is working on a document on agricultural labour issues to send to the EU Commission.

In Morocco, National Federation of the Agricultural Sector (FNSA) pointed out that the conditions for compensating workers who lost jobs due to the pandemic exclude hundreds of thousands of farmworkers, packing station workers and fisherfolk, and called for compensation for these people and adequate protection for those who continue to work on the farms.

In India, the lockdown was hastily leaving little time for people to prepare or move to rural homes. The worst affected were millions of casual workers, migrants, and the landless in the cities. These groups of people needed adequate time to get back to the villages. Only a few managed, millions remain stuck in cities without any income or food. The situation is dire. Some agricultural workers have resorted to walking hundreds of kilometres to work in the fields. Thousands of Nepalis working in India are risking their lives, crossing the borders and rivers to go back to their villages. In Bangladesh, agricultural workers and casual workers engaged in informal work are affected too, require urgent assistance in the form of income guarantees and unconditional cash support.

Poor access to proper housing worsen the plight of the vulnerable

In Bangladesh, as in India, most people do not have access to adequate housing, and this makes the prevention of COVID-19 very difficult. Access to health by the poor is difficult, as health services are privatised. This situation also affects some African countries such as Kenya and South Africa. These, too, have a considerable population who dwell in the slums.

Remittances cut off

The travel restrictions have meant that most low-income families are not able to access cash remittances from relatives in diaspora. In Nepal, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, most people get money from external remittances from the Middle East and European countries. It is a challenge for all these immigrants to support their families now.

Racism, Xenophobia, and Islamophobia on the rise

Some right-wing politicians, taking advantage of the confusion and panic, stoked Islamophobia and xenophobia. Many migrant workers who facially resembled Chinese from the North-eastern states of India faced increased racist attacks. The caste struggle makes the situation complex as most of the landless people and daily wage workers are from the lower castes. People are associating coronavirus to Chinese, and this has led to increased attacks on Asians in the US. Such attitudes are likely to spread to Africa following recent reports mistreatment of Africans in China as authorities imposed strict testing regimes.

Promoting food sovereignty to fight COVID-19 in Palestine

Israel, an occupying power, is not being held responsible for the lives of 300,000 people living in area C. It is abdicating its primary responsibility towards the health rights of 50,000 Palestinian workers working in Israeli industrial, agricultural, construction, and services sectors. The COVID-19 breakout comes under fragile food security levels where about a third of the population has no means to afford nutritious food, especially the women headed families. Union of Agricultural Work Committees (UAWC) believes that this is the time to promote food sovereignty to maintain food security for the Palestinian people and provide nutritious food. They launched a Campaign “Go back to your land and cultivate it. UAWC plans to distribute more than 300,000 vegetable seedlings to home in area C and other West Bank areas. So far, about 178,000 seedlings were distributed in early April to over 1,900 gardens in 55 rural communities.

In Kenya, Kenyan Peasant League is distributing and promoting local seeds. EcoRuralis, ECVC member in Romania, is distributing seeds to support farmers.

Practical solidarity

In Bangladesh, Bangladesh Agricultural Farm Labour Federation (BAFLF) is doing Community-based organising of migrant workers and distributing food rations. In Pakistan, Pakistan Kissan Rabta Committee (PKRC) is running a relief program to support farmworkers and urban poor by distributing food, dry ration, and other essentials.

In India, Bhartiya Kisan Union (BKU), Karnataka Rajya Raitha Sangha (KRRS), Tamilaga Vivasaiyagl Sangham (TVS) are working with local authorities to resolve the problems of access to regulated farmers’ markets. They have called for community solidarity to help agricultural workers with grains and vegetables, and to help stranded migrants. They are promoting barter system in villages.

In Sri Lanka, Movement for Land and Agricultural Reform (MONLAR) is calling on the government to support the peasants and labourers with food rations and pensions and to stop plantations from forcing workers to work.

In Brazil, the Landless Workers Movement (Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais sem Terra (MST) has been distributing food produced by its cooperatives to hospitals and needy people during the COVID-19 crisis. Over 500 tonnes of healthy food has been distributed across the country by the teams of landless workers from settlements and camps. What MST has done clearly shows the benefits and results of popular agrarian reform.

Education

The children of peasants are disproportionately affected by school closures due to lockdown measures. However, some children continue with schooling online. Most peasants lack access to information and communication technologies (ICTs). MST and Latin American Institute of Agroecology are using radio to communicate and keep the schooling activities running respectively. Many other members of La Via Campesina are helping to build awareness among the peasants and the communities in the countryside on COVID-19. In Puerto Rico, La Organización Boricuá de Agricultura Ecológica prepared an infographic on COVID-19 health recommendations to create awareness among peasants so that they continue to produce food safely.

Continuing the Struggle for a better future and food sovereignty

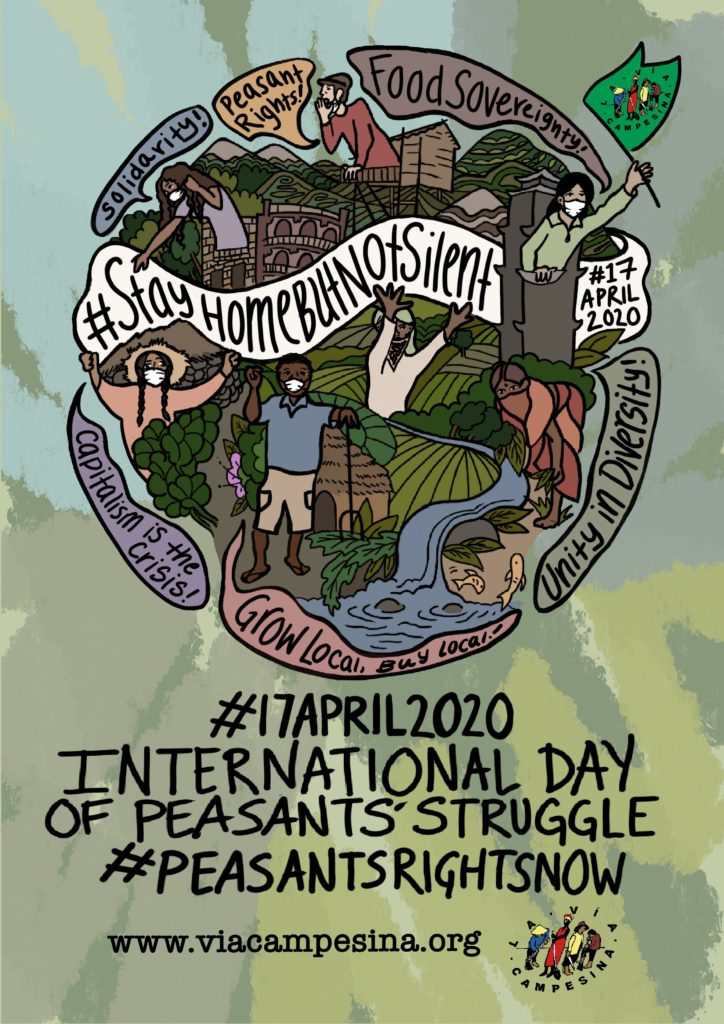

On April 17th, the International Day of Peasants’ Struggle, La Via Campesina mobilised its members, allies, and friends to do #StayHomeButNotSilent actions during the COVID-19 lockdown measures. On this day, La Via Campesina keeps alive the memory of #EldoradoDosCarajás in Brazil and continues the fight against Corporate and State impunity. For Via Campesina peasant rights are important to building a better future based on Food Sovereignty principles. This means strengthening and rebuilding the local food systems and shaping a new model of economic and social relations based on dignity, equity, and solidarity.

This post is also available in Français.