Inter-American Court rules on the murder of rural worker Antônio Tavares

From Brasil de Fato | Rio de Janeiro (first published on March 13, 2024)

On Thursday (14), the Inter-American Court of Human Rights will make public its ruling against the Brazilian state for its omission and failure to hold the public agents involved in the murder of rural worker Antônio Tavares accountable. He was killed by the Paraná State Military Police on May 2, 2000, in an action that left 185 other members of the Landless Rural Workers’ Movement (MST) injured.

The Court, linked to the Organization of American States (OAS), has been analyzing the case since February 2021. In June of 2022, hearings were held in Costa Rica in the presence of Tavares’ widow, Maria Sebastiana; Loreci Lisboa, a survivor of the attack; organizations representing the victims; and members of the governments of Brazil and Paraná state, representing the Brazilian state.

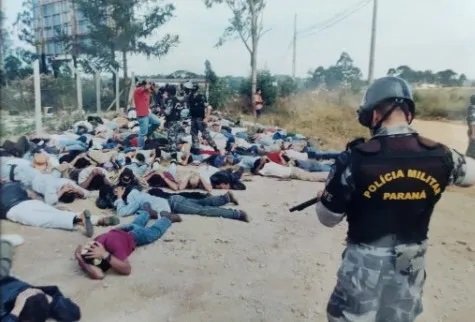

The peasant’s killing happened during the Agrarian Reform March, organized in Curitiba (Paraná’s capital city) to celebrate the International Workers’ Day of Struggle. A group of more than 1,500 MST members were repressed by the police when a troop of officers blocked the BR-277 highway and used firearms to prevent a motorcade of 50 buses from arriving in Curitiba.

Antônio Tavares, 38, was married and had five children. He was shot and died after he and other passengers got off one of the buses. During that same attack, other workers were injured and received no medical care.

For the MST, the episode is “one of the most emblematic moments in the criminalization and use of violence against the struggle for land.” The Brazilian judiciary power dismissed the case. In the face of impunity, it was presented by the MST and the organizations Terra de Direitos and Justiça Global to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR). It was also requested to be presented to the Inter-American Court.

Terra de Direitos’ international advocacy coordinator, Camila Gomes, points out that Brazil has committed itself to respecting an extensive list of rights and, in the event of a violation, mobilizing all the institutions to promote reparation – which did not happen in Tavares’ case.

“For a case to reach this level – being condemned by an international court – it needs to be a serious and very emblematic case of rights violations, but it also needs to have had no adequate response within the country itself. In other words, these are serious cases to which national authorities and the country’s institutions have failed to respond,” he says.

The organizations that filed the complaint highlight that the context at the time in Paraná state was one of intense violence targetin rural workers, with the criminalization of their struggle for the right to land, in addition to threats and murders, such as those of Diniz Bento da Silva (known as Teixeirinha), Sebastião Camargo and Sétimo Garibaldi. The country has already been sentenced by this same international court for Garibaldi’s murder.

Trials in Brazil

A military police investigation launched days after the murder of Antônio Tavares was closed on the grounds that the officers acted in “strict compliance with their legal duty”. The Paraná State Court of Justice closed the criminal proceedings in the case, claiming that the Military Court had already closed the case.

The petitions to the international court were filed after the possibilities of achieving justice through the local legal system had been zeroed. Since Brazil has voluntarily submitted to the Inter-American Court, the country must abide by the decisions taken and cannot appeal them.

Brazil’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs will formally accept Thursday’s ruling. However, the ruling is addressed to the Brazilian state as a whole, which includes the federal level, states and municipalities. In all these spheres, different bodies may have to comply with parts of the ruling. Therefore, this will be closely monitored by the Court.

“[The Court] will establish specific measures regarding the victims, but it will also indicate the so-called guarantees of non-repetition: structural measures that the state needs to adopt so that these violations don’t happen again to other people,” explains Camila Gomes.

By Felipe Mendes

Edited by: Matheus Alves de Almeida