Brazil: Since the return to democracy there have been nearly 2,000 political assassinations in rural areas

Records from the Pastoral Land Commission (CPT) show that, since 1985, 1,833 peasants and leaders of the struggle for agrarian reform have been assassinated in conflicts over land, while during the same period of time large land estates have grown by 375%.

(April 25 , 2017) The year 2016 was marked by setbacks all over the country. In the rural areas, the situation did not differ: the number of assassinations caused by land conflicts was higher than it had been in 13 years. With 60 deaths (20% more than in the previous year), 2016 became the most violent year in the countryside since 2003, when (according to the Pastoral Land Commission’s report that was published in 2016) 71 people were murdered in the course of their struggles for land reform and for the protection of their traditional territories.

As in previous years, incidents of violence were concentrated in the areas surrounding Amazonia. 49 out of the 60 assassinations took place in this region. With 21 deaths, Rondônia was the most violent state. Maranhão was in second place with 13 assassinations. The state of Pará, previously in first place, was third, with 6 deaths. There were 3 assassinations in Tocantins, and Amazonas. Alagoas and Mato Grosso each had 2 deaths. The region with the most conflicts over land was the North-east; it was followed by the Centre-West, the South-East, and, in last place, the Southern region.

According to the report, disputes over land and water resources are the chief causes of violence in the countryside. In areas where there is an expanding presence of agribusiness, mining installations, and large infrastructure projects conflicts are intensified.

The victims include Indigenous people, Quilombola[1] leaders, peasants, and trade unionists. The CPT’s study emphasizes three emblematic cases: the assassination of the activist Nilce de Souza Magalhães in Porto Velho (Rondônia); and the assassination of the peasant Ivanildo Francisco da Silva in Mogeiro (Paraiba), and of the Indigenous man Clodiode Aquileu de Souza in Caarapó (MatoGrosso do Sul).

(Nilce, our comrade who reported and protested against human violations linked to the construction of the Jirau dam in Porto Velho, was assassinated in January last year).

(Nilce, our comrade who reported and protested against human violations linked to the construction of the Jirau dam in Porto Velho, was assassinated in January last year).

The most shocking case was the assassination of Nilce, a member of the Movement of People Affected by Dams (MAB). Nilce, who was well-known for her leadership in the citizens’ movement against the the construction of the Jirau hydro-electric dam, disappeared on January 7th, 2016. Five months later (in the middle of June), and only 400 metres away from the fishing community in Mutum where she lived, she was found, with stones tied to her hands and feet, at the bottom of the reservoir controlled by the dam. Nilce’s two daughters recognized their mother’s watch and her clothing.

“It is easy to grasp if we look at the map of deforestation in the Amazonia Legal Region (the 9 states in the Amazon basin). Deforestation is increasing in Rondônia and advancing rapidly into other areas.”

Another ruthless murder, which caused shockwaves at the national level, took place in a rural area of the state of Paraíba, a region of great historical importance for the peasant struggle in Brazil. On April 7th, 46-year-old Ivanildo Francisco da Silva, a member of the Padre João Maria settlement, was shot in the head with a 12 calibre rifle at his home in the rural area of the municipality of Mogeiro. His body was found the following morning by his wife. His one-year -old baby daughter, who had been with him when he was killed, was still at his side; she was crying and covered with blood. Ivanildo and other members of the settlement had already been victims of an armed attack, which took place in 2015 and which was paid for by landowners in the region. At that time, seven gunmen were arrested but they were released after payment of bail.

In the interior of Mato Grosso do Sul, near the municipality of Caarao, in June, the assassination of the young Guaraní-Kaiowá man, Clodiode Aquileu Rodrigues de Souza exacerbated the conflict between the Indigenous people and the region’s large landowners. In order to lay claim to their ancestral lands (which had been surveyed and demarcated by the National Indian Foundation -FUNAI), the Kaiowá were occupying the Tey’ikue reserve, on which the (privately-owned) “Yvu” Farm (Fazenda) is situated. They were surrounded by 70 armed and masked landowners who, according to eyewitness accounts and to the hospital report, fired at them with live ammunition. The young health worker was killed, and five other Indigenous people, one of them a child, were imjured..

The methods used by large landowners to intimídate the Indigenous communities in the region are not limited to armed conflicts. In July, the First Federal Court of Dourados granted precautionary measures in favour of the local indigenous community; the large farms in the surrounding area were prohibited from spraying toxic agricultural chemicals, whether by air or from the ground, at a distance of less than 50 metres from the reserves. The case had been dragging on since 2008, when the Indigenous people went to court and won the right to occupy two properties forming part of the legal reserve, and the landowners resorted to using planes instead of tractors to spray their soya and rice plantations.

VIOLENCE IN THE COUNTRYSIDE: THE PRINCIPAL ELEMENTS

Between 1964 and 2016, 2,507 men and women were assassinated in rural areas in the regions of Brazil. (These figures were compiled by the Pastoral Land Commission, which has made a systematic study of the incidents that have taken place since 1984, and the Landless Workers Movement (MST), which assembled data on the years before 1986.) One of the most violent periods was the decade of the 1980s, when Brazil returned to democracy. The 1980s were marked by the founding of the MST and by an increase in social mobilisation and in struggles for a more democratic system of landholding.

Following the restoration of civilian government, the CPT recorded 1,833 assassinations in rural areas between 1985 and 2016. In other words, the number of recorded deaths resulting from rural conflicts was three times higher after the return to democracy than it had been in the years preceding the return. That does not mean that there were more deaths during the period of democratic government, but rather that records from the earlier period are unreliable. It only illustrates the significance of the conflicts that have taken place since 1985.

An Indigenous man displaying the cartridges that were found after the attack by the landholders. Published by Ruy Photo

An Indigenous man displaying the cartridges that were found after the attack by the landholders. Published by Ruy Photo

During the 90s, there was a decline in the number of deaths, and in 2000, there were 21 recorded assassinations. How can we explain that this number doubled in 2015 (with 50 recorded deaths) and tripled in 2016?

For CPT National Coordination member, Thiago Valentim, there are three main reasons for the increase in the number of conflicts. Firstly impunity, but, he stressed, this only means impunity “with regard to rural conflicts, given that our penal system is one of those with the highest rates of incarceration”. Secondly, the dismantling of public institutions and the absence of a government policy for democratising landholding. Valentim recalls that in the past several years there has been little investment in agrarian reform. “It has declined to the point where there were years when the government did not expropriate any land” for agrarian reform.

The coordinator believes that this is why the number of conflicts has risen. Because there are communities that are engaged in struggles for land, and when governments fail to act, “it is the social movements that come directly into conflict with the large landowners”. The third reason given by Valentim is the growth of agribusiness, “the continued expansion of large corporations and infrastructure projects” that are drawn to the territories of traditional communities because of the wealth of the natural resources they contain.

“Four workers in this region were killed, and up until now there has been no proper investigation. Those responsable for these murders are civil and military police personnel assigned to the region.”

The Executive Secretary of the Indigenist Missionary Council (CIMI), Cleber César Buzatto, believes that the main cause of violence against Indigenous people is the slowness and virtual paralysis of administrative procedures for land demarcation. “This factor contributes a great deal to the increase in tension and in conflicts between peoples. Another aspect is that agribusiness has become increasingly organised; its systematic onslaught against the rights of the peoples is more coordinated and more violent. In recent years, the Ruralist Bench has been particularly active, using legislation, such as PEC 215 (a constitutional amendment, put forward by Liberal Party congressional deputy Amir Moraes de Sà from Roraima, that transfers responsibility for the demarcation of Indigenous land from the executive branch of government to the Congress) as a means of opposing Indigenous rights. Many members of Congress (deputies) are making hate-filled speeches and fomenting violence against traditional communities and against the organisations supporting them, and this has led to an increase in armed attacks against Indigenous leaders and their allies”, Buzatto emphasized.

According to the records of the Executive Secretary of CIMI, between 2015 and 2016 there were more than thirty armed attacks by paramilitary agents and hired gunmen acting under the orders of large landowners.

In the opinion of João Peres, the author of the book “Corumbiara: a buried case” (Corumbiara caso enterrado, editora Elefante) about the 1995 massacre of peasants at the Santa Elina estate, it is nothing new for Rondônia to be one of the most violent states. “The deaths have two causes: acts and omissions on the part of the government. He considers that one of the acts that particularly stands out is the construction of the twin hydro-electric dams (Jirau and Santo Antônio), which resulted in deforestation and opened the door to organised large-scale forest takeovers that the government found very difficult – and was even afraid – to deal with”. “It is also possible to point to the land speculation stimulated by the prospect of paving the BR 319 highway – at the very place where a number of emblematic leaders were assassinated”.

Peres emphasized that the assassinations occurred precisely where there is intensive logging and little oversight. “It is easy to understand if we look at the map of deforestation in the Amazonia Legal region. Deforestation is increasing in Rondônia and advancing rapidly into other areas.” That is why people were assassinated in the Vale do Jamari, which in the 21st century seems to have taken the place of the Southern Cone of Rondônia as the most dangerous part of the state. Violence against the social movements is fuelled by inadequate investigation procedures. Since it is the landowners who are in charge of government institutions, it is obvious that the government will not take action to resolve the cases; on the contrary, it will work to see that they go unpunished”.

The author recalled that during the dictatorship Rondônia attracted both the large landowners and the landless, and that, even after five decades of migratory ‘boom’, this mixture “continues to be explosive”.

PRISON AND PERSECUTION

The violence in the countryside that was resported in 2016 did not begin or end in that year. Political persecution and arbitrary imprisonment are a reminder of the 1964 dictatorship that is being reinvoked at the present time. In November 2016, in a Paraná Civil Police operation named “Operation Castra”, eight members of the MST were arrested in the Quedas do Iguaçu region. These peasant members of the MST, who were accused of belonging to a criminal organisation and of “committing acts of extortion against settlers” were placed in detention; they continue to be held in prison.

In the opinion of Geani Paula, coordinator of the MST in Paraná, the reasons appearing in the imprisonment order are “accusations that are out of touch with reality”. The region has been marked by conflict since 2014, when approximately three thousand families occupied land belonging to the Araupel Company. The land in question had been classified as having been obtained by means of falsified documents (griladas) [2], and the Federal Ministry of Justice had declared it to be public land that belonged to the Union (the union of the federal district, the provinces, and the municipalities of Brazil), land that should therefore be included in the agrarian reform programme.

“In the region, four people have already been killed, and until now there has been no proper investigation. Those responsable for the murders are civilian police and military personnel who are active in the region”, Paula complained.

LAND CONCENTRATION AND THE FAILURE TO DEMOCRATISE LAND OWNERSHIP

Ihe democratisation of the voting system outpaced democratisation of the countryside.According to the report published by Oxfam Brazil (an organisation connected to Oxford University with branches in 94 countries), entitled “Fields of Inequality: Land, Agriculture, and Inequality in Rural Brazil”, land concentration is the principal cause of violence in the countryside. At the present time, the very large land owners, who make up less than 1% of the total number of Brazilian land owners, hold 45% of the whole rural area, whereas small land owners (those with less than ten hectares – approximately 24 and a half acres – occupy less than 2.3% of the rural area.

In January of this year, the Nucleus of Studies, Research, and Agrarian Reform Projects (NERA), which is linked to the UNESP Universidad Estadual Paulista), published a report emphasizing the problem of increasing land concentration in Brazil. According to the study, in the last thirty years there has been a 375% growth in the land area occupied by large estates. Their research calculates the growth, since 1985, of properties with more than 100,000 hectares.

According to the researchers, the pace of agrarian reform is not keeping up with the expansion of agribusiness. The territorial expansion of agribusiness can be ascribed to the use of falsified land titles and to the growth in foreign ownership. The research links foreign land ownership in Brazil to at least 23 countries, among which are the United States, Japan, the United Kingdom, France, and Argentina. “The main investments are in commodities: soya, maize, canola, rapeseed, sorghum, sugar cane, and tree monoculture, in addition to the production of genetically-modified seeds”, the report explains.

NEW AGRICULTURAL FRONTIERS, NEW CONFLICTS

According to Thiago Valentim of the CPT, the the exacerbation of the conflicts is more pronounced in the Northern region, because “there has a greater advance of capitalist interests, and because it is a very rich area where companies are buying large extensión of land”. He also signalled another very coveted area, which provides an explanation for the increase in conflicts in the North-east: the Matopiba Agricultural Development Plan (Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí y Bahia).

Valentim thinks that the region is a clear example of the campaign against traditional communities, which, after its previous expansion in the North, is now being extended, in a more coordinated way, to other parts of the country. The CPT’s report recorded dozens of cases of violence in Matopiba, such as armed conflict, the destruction of houses and crops, displacement, threats of eviction, and the blocking of access to water sources.

BLOOD-STAINED LAND

According to research conducted by the Pastoral Land Commission and the Landless Workers Movement (MST), more than 2,500 men and women were assassinated between 1964 and 2016, in all parts of Brazil. The decade of the 1980s, the time period when the country was returning to democracy, coincided with the worsening of violence in the countryside, with leaders being assassinated at the behest of landowners, mining companies, and large corporations. Despite occasional accusations brought against gunmen, those responsable were very seldom brought to justice.

On April 17th, 1996, nineteen landless workers were assassinated by the Military Police in an incident that became known all over the world as the Eldorado dos Carajás Massacre, which took place in south-eastern Pará. The MST members were taking part in a march to the city of Belém when the military police blocked their path. More than 150 military police personnel (armed with guns and live ammunition, and without any identification badges on their uniforms) had been called in to stop the march. What ensued was a repressive action of extreme violence. Two decades later, two of those who commanded this operation have been convicted: Colonel Mario Colares Pantoja, sentenced to 258 years, and Major José María Pereira de Oliveira, sentenced to 158 years. There was never any investigation of the evidence regarding the involvement of Vale do Rio Doce (which at that time was still a state-owned company) in transporting the troops from Paraupebas and Marabá , in a Transbrasiliana Company bus.

The name of the Transbrasiliana administrator – who took the order and who received the payment – is Gumercindo de Castro. The name of the Vale civil servant who contracted the bus company’s services is James. “How can you explain why a state-owned company contracted a prívate business to transport military police personnel who had been summoned to break up a public demonstration?” asks Eric Nepomuceno, the author of the book “The Massacre: Eldorado dos Carajás: A Story of Impunity”, published by Editorial Planeta. (“O Massacre: Eldorado dos Carajás: Uma história de impunidade” – Ed. Planeta).

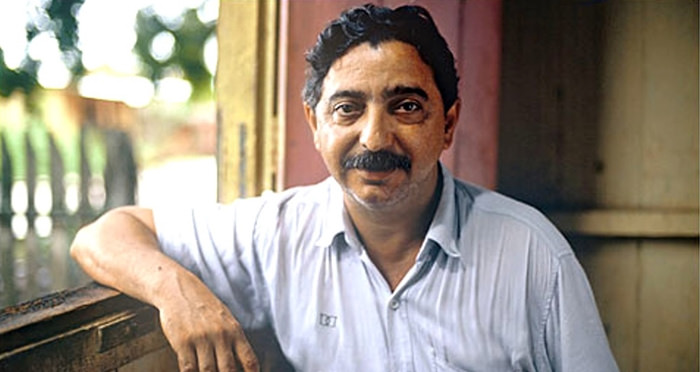

Memorial Chico Mendes/Divulgación

Memorial Chico Mendes/Divulgación

Francisco Alves Mendes Filho (Chico Mendes), leader of the rubber tappers movement and president of the Rural Workers Union of Acre, was assassinated on December 22nd, 1988, at the age of forty-four. He was shot to death by Darci Alves, who was acting under the orders of landowner Darli Alves. In 1990, both men were sentenced to nineteen years in prison, but they escaped in 1993 and were recaptured three years later. They were able to benefit from penitentiary models involving semi-open prisons and house detention.

CPT/Divulgación

CPT/Divulgación

The North American missionary, Dorothy Mae Stang, a social and environmental rights activist and the defender of an environmental sustainability project for Amazonia was assassinated, at the age of 73, on February 12th, 2005, in the interior of Anapu, near the Trans-Amazonian Highway in Pará. Dorothy Stang, a naturalised Brazilian citizen, had been living in the region since the 1970s. She was engaged in the struggle for the creation of the Esperanza Reserve, an Incra (National Institute of Colonisation and Agrarian Reform)[3] project, when she was captured by gunmen. Two of those involved in the crime, Vitalmiro Bastos de Moura and Regivaldo Pereira Galvão, are at liberty.The gunmen who carried out the crime, Clodoaldo Batista and Rayfran das Neves Sales, received prison sentences of 18 and 27 years respectively.

Greenpeace/Felipe Milanez

Greenpeace/Felipe Milanez

The farming couple, José Claudio Ribeiro da Silva y Maria do Espírito Santo da Silva, were assassinated in the morning of May 24th, 2011, in Nova Ipixuna in the south-east of Pará. On December 6th, 2016, José Rodrigues Moreira, the landowner who ordered the killings, was sentenced to 60 years by the Belém Court. Zé Claudio and Maria were environmentalists and forest product harvesters (extractivistas) and they publicly decried the illegal land take-overs and unlawful deforestation taking place inside the agro-forestry (agro-extravista) settlement in their local area.

Written by: Cauê Seigner Ameni (De Olho nos Ruralistas – a journalistic observatory on agribusiness in Brazil)

Translated into Spanish by: Amanda Verrone

[1] An identity referring to “quilombo”, a term derived from kimbundu, an African language belonging to the Bantu linguistic family, which is understood nowadays in Angola. In Brazil, the word was given a new meaning in connection with the repressive apparatus for capturing individuals or groups fleeing from slavery. In Brazilian colonial legislation, the term ‘quilombo’ designated any group of more than five Black people who were found gathered together. Thus in Brazilian history, Quilombolas are the people who expressed Black resistance to slavery.

[2] The illegal appropriation of land. ‘Grilagem’ is a longstanding practice of forging or falsifying documents related to land ownership, in such a way as to make them appear old, in order to obtain illegal possession of tracts of land. The term has its origin in the practice of putting the falsified documents in a box containing grasshoppers. After a time the effect of the grasshoppers was to make the documents look old – to give them an appearance of antiquity and thus of apparent authenticity.

[3] National Institute of Colonisation and Agrarian Reform (Instituto Nacional de Colonización y Reforma Agraria)

Source:mst.org.br