Within the framework of our strategy of formation/training, information and political analysis in defense of Food Sovereignty and Peasant Agriculture, with the slogan “Sow the seeds of struggle and resistance, and cultivate our rights!”, we share a second report on the COVID-19 and the situation of the peasantry.

It has been five months since most countries imposed lockdown measures, including travel restrictions both within and across borders, to control the spread of COVID-19 pushing millions of hungry people over the edge. During this period, tens of millions of people have contracted COVID-19, and over half a million people succumbed to death.

In June, some countries started easing the lockdown measures as the “curve of the infection” flattened and began to drop. Once again, urban streets started to teem with life, and many people were eager to catch up on many activities. However, this was short-lived as COVID-19 cases started to increase due to poorly implemented easing of lockdown restrictions by the governments. Indeed, COVID-19 has shown that we can no longer return to business as usual, that we have to change how we live and interact as a society. It is time to transform.

We are all suffering from the deepening social, political and economic crisis of the coronavirus pandemic. Because of the pandemic and its restrictions, hunger and poverty, which were already increasing due to the economic crisis caused by the decaying monopoly capitalism, are worsening. The scourge of the pandemic has not spared both the rich and the developing nations. For instance, in India, South Africa, Brazil, and many rich countries, the number of hungry people has dramatically increased and has become a new hunger hotspot. This pandemic has exposed and intensified the vulnerabilities and inadequacies of the global food system controlled by big companies. The United Nations reported that about 130 million more people would go hungry in 2020. Tens of thousands of people will likely die globally from hunger linked to COVID-19 per day by year end more than would die from the disease itself. The children will be worst affected. About 6,000 children could die every day from preventable causes due to disruptions to essential health and nutrition services.

Despite this, the accumulation of wealth by those at the top increased during this pandemic. Big companies have paid out billions of dollars to shareholders since January. The world witnessed the birth of the first trillionaires, which included Amazon owner Jeff Bezos. This is happening when unemployment is record high globally. Joblessness and hunger among the urbanites have increased sharply because the response from governments has been not enough and a bit too late. Again, limited capacity and lack of preparedness to deal with the pandemic implications delayed the provision of relief to their needy citizens. However, this is not the case with the rich as they have facilities to access support. The rationale, though not true, is that the big companies will keep people in jobs and hopefully create more to address rising unemployment. They received the bulk of support in the form of economic stimulus packages, tax relief, etc., timeously. This behavior of our governments has convinced us, the peasants, working class, the poor and other vulnerable groups in this pandemic that we are alone in the deep waters. Many are being swept away. So our resistance and solidarity are important because we need to transform this system.

Anti-peasant measures and increased militarisation

The lockdown restrictions are disproportionately enforced, affecting the most the peasants and their communities, poor and the working class. Their cries for help continue to be ignored by the governments. Instead of providing more health centres to test and care for those infected in the countryside, most countries have militarized the lockdowns. The solidarity actions by peasants and the poor to care for and meet the needs in their communities are under surveillance and sometimes, violently crushed. For instance, in Chile, the state security apparatus has been detaining, beating and harassing the volunteers of community-led soup kitchens feeding the hungry. How can such initiatives filling the gap to prevent widespread hunger be criminalized? This just shows that governments are neither listening nor worried about us but focused on their survival, and view such initiatives as mobilization spaces against their rule. In Colombia, increased militarization of its territories instead of promoting peace is a cause for concern. Between January and mid-July, 166 social leaders and human rights defenders, and 36 ex-combatants were murdered.

In the Philippines, the security forces are lenient to mining companies that continue mining activities. At the same time, strict checkpoints discourage peasants from moving, some of whom have to travel a distance to reach their farmlands. In Thailand, agriculture is not a top priority of the government’s aid scheme, but manufacturing and tourism. Some government agencies have used the enforcement of emergency decree to violate the peasant’s rights. For example, the Department of Irrigation is forcefully evicting villagers in the land dispute with the Department.

Some countries are using the economic and political fragility due to the pandemic to reform labour, land, and essential laws related to foreign direct investments to benefit the elites. This has been the case in India and Sri Lanka. For instance, the Indian government has taken measures to relax existing laws around land acquisition, labour rights, and agricultural commodities to encourage privatization and contract farming. Indian farmers in Karnataka have opposed through street protests these attempts. In Brazil, the president, Bolsanaro, continues to deforest the Amazon to expand large scale farming, dispossessing the indigenous people of their territories. His government is currently evicting hundreds of landless families from Quilombo Campo Grande camp in the municipality of Campo do Meio, in the state of Minas Gerais. The camp is home to 450 families who have been living, producing, and working there for over 2 decades. Since July, the families have faced increased daily harassment by the Brazilian police. Some have been arrested. President Bolsonaro promotes hatred against social movements, peasants, and blacks.

In South Asia, the pandemic is being used as an opportunity against food sovereignty and to push neoliberal, pro-corporate reforms. Countries like Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Nepal are looking towards international financial agencies for more loans. These will make lives of the peasants more difficult, just like what we witnessed during the austerity of economic adjustment programmes of the ’80s and ’90s. This is what we see happening with the situation of the “debt crisis” in Ecuador, Argentina, etc. Loans threaten the ability of the governments to strengthen their public policies, including health, and are a serious setback to peasants’ rights.

In Africa, South Africa recently secured a US$4.3 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund for the balance of payment needs. This support means that the country with the highest colonial and racial land inequalities in Southern Africa rules out redistribution from rich to poor and will lead to more human suffering. Wealth inequality is high too. The top 10% owns 93%, while the remaining 90% of South Africa owns a paltry 7% of the country’s wealth. Over

In Latin America, particularly countries that adopted neoliberal policies have been affected the most by the pandemic. Because of these policies, which led to cut in public spending in social services, the health sector capacities are limited and strained, unable to cope with the coronavirus crisis. Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Peru, Ecuador and Panama are the most affected and also have high levels of corruption. Unemployment and poverty soared in the last five months. The economies of Latin American and Caribbean countries have contracted by almost ten percent. However, some countries such as Cuba and Nicaragua have fared better because of their pro-people policies. Both countries managed to contain the spread of the virus, while at the same time ensuring that their populations are adequately fed. Strong local food systems and the autonomy of peasant farms are the reason. Their governments are committed to food sovereignty and do not depend on global food systems to feed their populations. In Venezuela, the peasant producers’ alliance (Alianza Productiva Campesina) is a concrete way to guarantee food sovereignty and the rights of the peasants.

In Africa, the modernization of agriculture has gathered more steam. The pandemic and the imminent food insecurity have created opportunities for Green revolution agencies and some philanthropic organizations to push for the widespread use of agrochemical inputs, GMO seeds, and to digitalize agriculture. For instance, Alliance for Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) says in its May 2020 situation report it … “continues to partner with smallholder farmers and agribusinesses to strengthen the resilience of food systems while providing critical guidance to African governments for decision making.” AGRA is knocking on the doors of African policymakers to present them with solutions “…to avoid the potentially disastrous impact of the virus on food systems…” However, we all know this is not true. The access to chemical inputs will make peasant agriculture untenable and expand agricultural commodity production mainly for exports. Peasant farmers are slowly being reduced to “label/prescription” readers to farm “productively using chemical fertilizers, pesticides, hybrid seeds etc.”, no more innovation. This should not be allowed to happen. As La Via Campesina, we need to mobilize and push back these efforts to weaken and extinguish the food sovereignty of African peasant farmers based on agroecology, and traditional knowledge systems and farm-saved seeds.

In Europe, the European heads of State recently agreed on the budget for the recovery plan, from which the Common Agricultural Policy allocations failed to address the interests of the peasant farmers. Peasant agriculture in Europe has been hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, the prices in the livestock and dairy sectors have dropped due to the collapse of the market and increased surpluses as demand fell. The European Coordination Via Campesina (ECVC) is urgently calling for action to address the situation, and regulate and stabilize the market and producer prices against market volatility. European Commission’s support for the sector is inadequate. The Commission is more concerned with production and not with producers, at a time when more than 1,000 farmers per day leave the profession in Europe. Indeed, this is one of the major obstacles to young people entering into farming.

In Asia, Bangladesh’s fiscal stimulus has only helped big businesses and industries, and agriculture is neglected. As a result, poverty increased from 21 percent to 40 percent, and about 37 percent of small farmers (paddy, fishers, dairy) completely lost their investments. In Sri Lanka, many rural people are committing suicides due to failure to repay microfinance loans. The Movement for Land and Agricultural Reform (MONLAR) is campaigning for debt relief and the abolition of microfinance loans.

Where support programs exist for the poor and small scale farmers, such as in Vietnam, Philippines, etc., the criteria for selecting the beneficiaries exclude most of those in need. In Japan, family farms received less support than corporate farms, and support was only given to farmers who could prove that their sales dropped by 50%. Many farmers struggle to collect full information on the impacts in order to determine what measures are needed for their recovery.

More economies opening up to attract foreign investments: Free Trade Agreements

Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) negotiations continue in Asia, Europe, the Americas, and Africa. Some are ready for signing, while some recently came into effect. In July, the new free trade agreement of the United States, Canada, and Mexico, T-MEC, came into force. This will worsen the crisis that is suffocating the Mexican countryside in the form of high seed prices and the growing monopoly and intellectual property over certified and hybrid seeds. Whoever controls the seeds, controls the food. T-MEC will privatize more seeds and medicinal plants in Mexico, as this agreement requires the country to comply and align, among other treaties, with the unfavourable and destructive International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV-91). UPOV-91 is a product of transnational corporations and its imposition in Mexico is a further attack on the peasantry way of life- the collective ownership of traditional knowledge, seeds, healthy food production, etc.

In Asia, China and the US are elbowing each other to gain access to the regional economies for trade. Sri Lanka is trying to sign FTAs and is relaxing foreign investment laws related to land and agriculture. Nepal, too, is trying to raise more fiscal resources by opening the economy to foreign investments.

The European Commission is preparing the EU-Mercosur Free Trade Agreement for signing. If signed, the agreement will cause environmental destruction (of the Amazon forest), worsening the climate crisis and human rights violations with impunity through an export-oriented agricultural policy. In France, peasants and activists denounced the likely vote’s hypocrisy in favour of the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), an agreement too, which will worsen the climate crisis.

More exploitation of migrant workers: low wages and no protection

Millions of workers have now been discarded and thrown into the ranks of the unemployed. Those still employed have precarious working conditions, mostly on a contract basis. This has been the case with migrant workers in Canada, the United States of America, some western European countries, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, South Africa and many other countries that rely on such labour. For example, in Canada, more than 400 migrant farm workers tested positive with COVID-19 across Southern Ontario due to overcrowded, unsanitary housing, unsafe working conditions, and a failure to quickly identify and isolate infected workers. National Farmers Union (NFU) has joined calls for regulatory changes so that migrant workers can change jobs without the threat of deportation, have full access to health care and other employee benefits, and be granted permanent resident status. In US, farmworkers, mostly migrants, also have limited protection against COVID-19. They continue to work because they fear deportation if they register to receive free medical care, and victimization by crew bosses who punished them by cutting their hours or days. If they do not work, it means no money and food.

With regard to protecting agricultural workers against the pandemic, the European Commission has failed to ensure that the Member States enforce its guidelines and act concretely on the ground to prevent and fight exploitation. Migrant and seasonal workers still face exploitation and exposure to COVID-19 in Italy and other EU countries.

No Remittances, more dependents suffering

Measures restricting the movement of people has hit hard on cash remittances from migrant workers. Many have lost their jobs and can no longer afford to look after their families. Seasonal workers, too, are in the same predicament as migrant workers. Many of them were forced to leave the urban areas to return to their villages. This massive and unplanned influx of migrants has increased household food needs, while local restrictions reduced their ability to farm to fill the food gap and the related expenses.

Women and children are among the severely hit due to the pandemic. The cases of domestic violence have drastically increased during the lockdown, a clear sign of the patriarchy and machismo entrenched in nation-states, which do not protect women’s lives or even defend fundamental human rights. The United Nations estimates that over 10,000 more children will die per month as many farming communities are cut off from markets to sell or buy food and isolated from health centres.

Strengthening Solidarity in COVID times

Globally, the peasants, activists, and their allies are engaged in acts of solidarity to resist the State and the big businesses’ repressive actions. They have also joined hands to support each other to strengthen food sovereignty and provide protective materials against COVID-19. They are also maintaining social distancing while working and producing food. This is what some peasant leaders have called “productive isolation.”

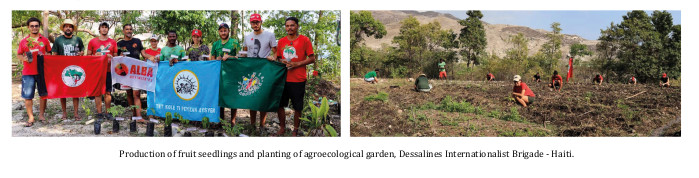

The Landless Rural Workers’ Movement (MST) Internationalist Brigades have been instrumental in the fight against COVID-19 in Africa and Latin America. The brigades redirected their actions to fight the coronavirus in the countryside and poor neighborhoods. They carried out activities to exchange experiences among peasants on the production of healthy food. They also donated food, seed, produced and distributed hygiene and protective materials in countries where they are based, such as Zambia, Venezuela, Haiti, etc.

The Union of Agricultural Work Committees (UAWC) continues to support thousands of families and small scale farmers in Palestine under its “United against COVID-19 emergency campaign.” About 9,354 families have been assisted, 1,490 hygiene kits, 358,000 vegetable seedlings, and 855 food parcels distributed. UAWC targeted families in remote and marginalized areas where no medical services exists or government health care is limited.

In Zimbabwe, the Zimbabwe Smallholder Organic Farmers Forum (ZIMSOFF) is working with allies and partners to stop the spread of COVID-19 in communities where the members reside. Various personal protective equipment (PPE) sourced with the support of WhyHunger has been distributed among farmers and their communities.

La Via Campesina issued several statements in solidarity with Mr. Junawal Bin Sukino, Chairperson of Serikat Petani Indonesia’s (SPI), Massa Kone the spokesperson of the Global Convergence of Land and Water Struggles in West Africa and, also denounced the US-backed Israeli attempts to annex the lands, waters, and territories of occupied Palestine’s Area C. La Via Campesina adds our voice to global opposition to Israel’s illegal annexation plans and reiterates the demand for an end to the entire Israeli occupation. Mr Junawal Bin Sukino was arrested for struggling against eviction in Napal Putih Village to make way for rubber plantation. Massa Kone’s home ransacked by armed people in Mali.

In Latin America, a Campaign of Solidarity with Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua against imperialist aggressions has been launched. It calls all popular sectors of workers, peasants, indigenous peoples, Afro-descendants, youth and black communities of our America and the world to join and fight against sanctions, economic, blockades, and all kinds of threats by the US and its allies.

In Brazil, the Women of the MST launched the campaign “Women without land: against viruses and violence”, to fight against the intensifying gender-based violence. The campaign includes other vulnerable groups such as the children, LGBT, and the elderly that are also are affected by this violence.

Various peasant movements and activists are organizing webinars to share and discuss issues affecting them, ways of resisting, and to build strategies and solidarity.

Is there hope?

The pandemic is provoking a response from below, from those most affected. Amid all the suffering, outbreaks of rebellion have sprung up in Africa, Europe, the Americas, and Asia. In the case of the US, the Black Life Matters (BLM) movement is the most powerful expression of popular anti-systemic response.

The pandemic has shown the importance of local food systems in feeding people and the urgent need to promote such systems where they exist and rebuild where they have been destroyed by many years of neglect under neo-liberal policies. It is the peasant’s food production systems that are feeding the people and preventing widespread hunger during this pandemic.

There is hope now that the wheels of societal change are beginning to turn faster during this pandemic. It is indeed time to transform. The rights of people, dignity, and solidarity, not profits, should be the foundation of the new society. Food sovereignty is the right and just path.